Introduction

Most backpackers improve their skills, pack weight, distance hiked per day, and other factors as they move through progressive stages of their passion. This story describes, in broad terms, seven arcs and five stages that we might have in common.

The seven arcs are:

- skills

- total pack weight

- gear complexity

- distance per day

- planned weather

- luxuries

- suffering

I could describe many other arcs; these seem to be common and illuminating.

Our five shared stages might be called:

- New Weekend Warriors

- Aspiring Thru-Hikers

- Lightweight Backpackers

- Gram Weenies

- Ultralighters

Some backpackers stop at a given stage, having reached their goals. Or they might “exit,” and choose to emphasize other factors besides pack weight or distance.

For many people, backpacking supports more significant activities like hunting, fishing, mountaineering, photography, and more. Striving for the lowest carried weight or the longest day’s hike is not that important to these people.

Stage 1: New Weekend Warriors

These backpackers carry a heavy pack on shorter trips while tolerating some suffering as they hike and camp. Their ranks are mostly younger people just starting out, often with borrowed gear. They typically go on weekend backpacking trips of one or two nights.

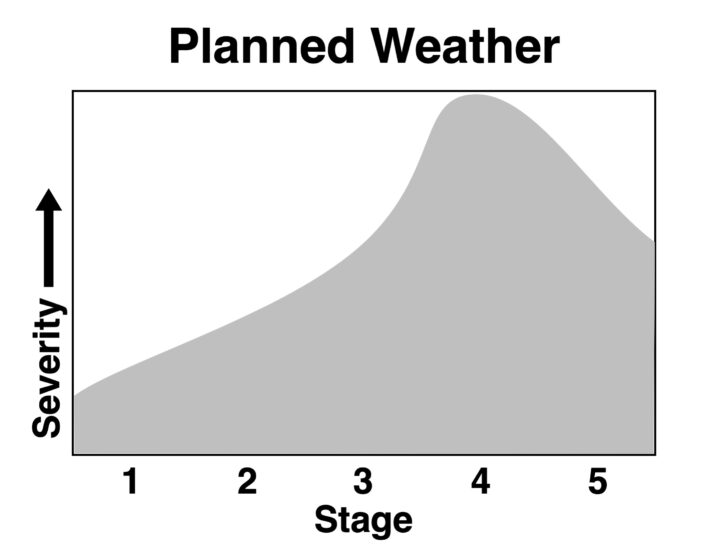

Backpacking skills and experience are usually slim to non-existent. They plan most trips for fair weather and often cut trips short when conditions turn bad.

Backpackers in this stage might slowly add weight, as they learn from sometimes painful experiences or good marketing, that they need a better first aid kit or party lights for their tent.

Often these trekkers struggle with taking too much or too little food, fuel, and water. If they run out on one trip, they almost always take too much on future trips. What some call luxuries, these trekkers consider necessities.

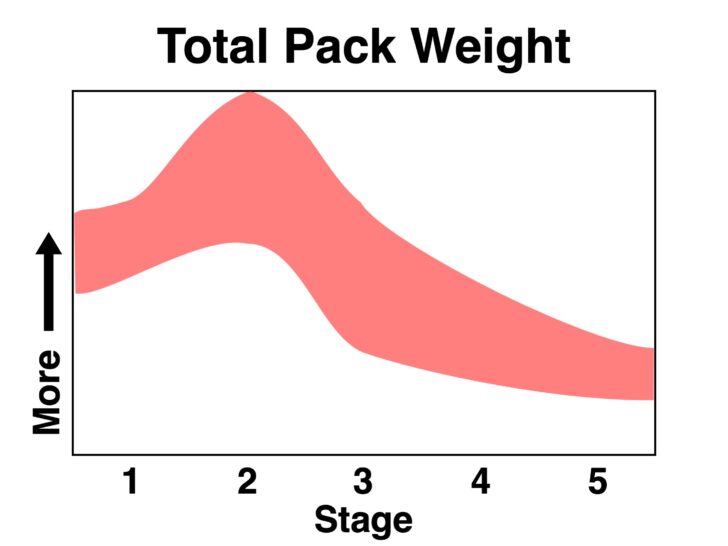

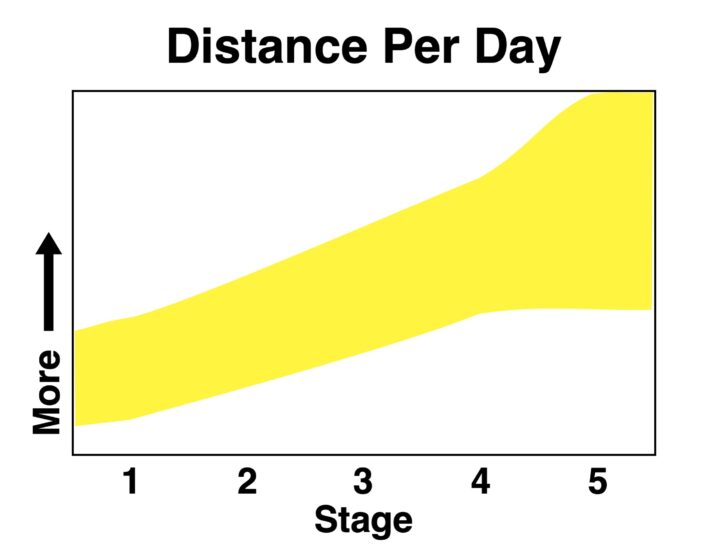

Total pack weight ranges from 25 to 35 lb (11 to 16 kg), with a base pack weight from 20 to 30 lb (9 to 14 kg). Most trips are 5 to 15 mi (8 to 24 km) per day.

Many backpackers stop at this stage, because their suffering is tolerable, and they are happy to be outdoors a few times every year. Gear is simply a means to an end.

Stage 2: Aspiring Thru-hikers

Some backpackers get more ambitious and want to tackle longer trips, getting deeper into wild areas, or spending several days at a favorite camping spot. A common pattern is to add more food and fuel to the gear they used for Stage 1. But they might also add more gear for birdwatching or taking kids along. Many become aspiring thru-hikers.

These backpackers often have some skills and experience – but not much. They plan trips for fair weather, though many push into the so-called shoulder seasons (spring and fall) by adding more or heavier gear. Sometimes, bad weather shortens their trip.

Because they are carrying more weight, these trekkers suffer more while hiking, though they might have a better time in camp or at that favorite trout stream.

At this stage, most backpackers have food, fuel, and water sorted out for shorter trips. But the learning curve restarts for longer trips, often with some hard-won lessons. They might add new luxuries like pillows and coffee makers.

Total pack weight often ranges from 30 to 50 lb (14 to 23 kg), with a base pack weight from 20 to 40 lb (9 to 18 kg). They might hike 15 to 20 mi (24 to 32 km) per day on some days during some trips.

A few people stop here, willing to suffer more for other benefits, but unwilling to dive into gear geekery. Many suffer so much that they go back to the shorter trips of Stage 1, while some give up backpacking entirely.

Stage 3: Lightweight Backpackers

Some Stage 1 and Stage 2 backpackers figure out that excess total pack weight is at the core of their suffering, or limits their adventures. These backpackers usually start by reducing the weight of their big three items – backpack, sleep system, and shelter. Yet after spending several hundred dollars replacing those items, they realize that carrying a 2 lb (1 kg) cook system or wearing heavy boots no longer makes sense.

This can lead to a sustained research-and-buying frenzy, pursuing lighter versions of everything they currently carry. They quickly reach diminishing returns on the amount of weight they can save per additional dollar spent. Yet backpackers in this stage frequently develop a kind of tunnel vision, focused on base pack weight while almost ignoring consumables like food, water, and fuel.

Their skills are roughly intermediate. Backpackers in this stage want to expand their trip repertoire to other regions and seasons, including early spring and late fall. Some add cross-country skiing, packrafting, or vlogging to their trips – with additional weight and new skill sets. The added mass of their passions encourages them to further reduce base pack weight.

Rather than buying all their gear from big box stores, they often start purchasing items directly over the Internet from smaller gear makers.

Total pack weight ranges from 15 to 35 lb (7 to 16 kg), depending on trip length. Base pack weight, usually tracked using complex spreadsheets, might range from 10 to 15 lb (4.5 to 7 kg). Daily distances over 20 mi (32 km) become much more realistic.

A lot of people stop here, content to suffer less while enjoying the outdoors.

Stage 4: Gram Weenies

Some Stage 3 backpackers choose to go further and overhaul their kit. Occasionally aspiring Stage 2 trekkers cruise through Stage 3 and into Stage 4 without pausing.

Rather than relying exclusively on marketing, reviews, and advice from others, backpackers in this stage often start experimenting. They swap tents for tarps and bivy sacks. Quilts might replace sleeping bags. They spend many hours contemplating frameless packs. But they can’t quite make the leap to stoveless trips after trying a few no-cook dinners.

New jargon like “EN ratings,” “hydraulic head,” and “CFM” peppers many conversations. Online they debate the pros and cons of DCF, silnylon, and silpoly. Gear storage and display take over entire rooms at home. Trip planning frequently involves agonizing decisions over which of several backpacks, tents, or sleeping bags to take. Non-backpacking friends and loved ones start rolling their eyes and avoiding certain topics.

Their skills are pretty good by now, and tackling winter trips, remote environments, and higher altitudes becomes possible.

A few become modders. They start by trimming excess bits and pieces from their gear to save weight and graduate to adding missing features after many hours of research and sketching. For a few, shedding weight becomes almost an obsession, removing clothing tags and extra inches (centimeters) of straps without mercy.

Some backpackers at this stage start making their own gear, out of frustration from not finding their idea of the perfect item, or out of fiscal necessity.

They analyze food for calories-per-ounce or kilojoules-per-gram, frequently at the expense of edibility or good nutrition. Stove fuel gets a similar treatment, followed by a flurry of stove buying, making, and testing. They still view water as a critical necessity, but usually, skip a detailed needs analysis.

Eliminating luxuries becomes a passion, often at the expense of a good night’s sleep or other necessities. They believe this added suffering is required to hit certain base pack weight goals.

Total pack weight might range from 10 to 25 lb (5 to 11 kg), depending on trip length. Base pack weight can start below 10 lb (5 kg). These trekkers may plan trips assuming 20 to 25 mi (32 to 40 km) per day, and occasionally might even hit 30 mi (48 km) per day.

Many backpackers stay in this level, with a constantly evolving gear selection, and frequent trips to the Backpacking Light gear swap forum.

Stage 5: Ultralighters

In this very small club, concepts like SUL (super-ultra-light) and XUL (extreme-ultra-light) become part of their online discussions. Arguments might break out over what counts as worn weight or carried weight. They discuss the latest fastest known times (always abbreviated FKT) on famous trails, including subtle distinctions between supported and unsupported trips.

The equipment they use often becomes a mix of MYOG (make your own gear), plus near-custom items purchased from very small cottage makers with delivery times measured in months.

Backpackers at this stage require a deep set of skills to use their gear safely, often honed over many years and long thru-hikes. They are usually comfortable hiking in all seasons, off-trail, and sometimes pioneering new routes. When carrying minimal loads, these trekkers might avoid the most severe weather.

Food and fuel weights are pretty dialed-in by now. At water breaks, cameling up (drinking a lot) and making large meals becomes the norm to reduce carried water weight. Backpackers in this level might allow themselves one luxury item, and highlight that in gear lists or social media posts.

Total pack weight rarely exceeds 15 lb (7 kg). Base pack weight varies, but for most trips rarely exceeds 10 lb (5 kg). Daily hiking distance is usually over 20 mi (32 km), often reaching 30 or 40 mi (40 or 64 km).

Other Observations

Most first-time thru-hikers on the Appalachian Trail or Pacific Crest Trail seem to be in Stages 1 or 2. With luck, early in their journeys, they get gear shakedowns from more skilled and experienced backpackers, so they can suffer less and be much more likely to finish. Much gear gets mailed home and new gear purchased or scrounged from hiker boxes. Successful thru-hikers usually end their trip in Stage 3 or higher.

Somewhere around Stage 3, many backpackers start realizing that what works well for others doesn’t always work well for them. But there’s often a phase marked by relentlessly searching for the perfect backpack, tent, sleeping bag, stove, etc. Most of these trekkers ultimately understand that there’s no such thing.

According to studies done by gear creator Michael Glavin, once people reach a sweet spot for total pack weight, further weight reduction brings many fewer benefits. A few backpackers figure that out for themselves and stop pursuing ever-lower pack weights.

At almost any stage, many backpackers stop obsessing over ounces or grams and realize that for just a little extra weight they can dramatically improve comfort, performance, safety, and other factors. Or they become content with good enough gear and focus on getting outside more often.

It’s important to understand that skills and experience are not directly linked. You can brush your teeth wrong for 25 years if you don’t know any better. Operating a complex stove might be easy in favorable conditions, but could be a major struggle the first time you try it while cold, wet, tired, and hungry.

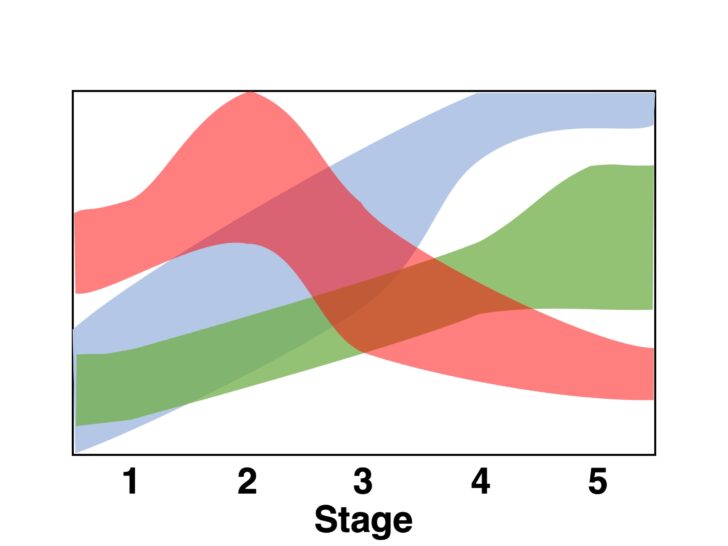

The Arcs

Now that we’ve set the stage, these backpacking arcs should make sense. I’ve omitted units on the vertical axis; the shape of each arc is more important than the precise values. Besides, everyone’s actual arcs will be different.

These arcs are graded on a curve: the range from bottom to top is not absolute, but relative to this discussion.

Most backpackers gradually acquire skills from a variety of sources, including the school of hard knocks.

While many books and online resources emphasize reducing base pack weight, it’s total pack weight that directly impacts your suffering and other goals. Near the end of a long trail day, your body doesn’t care if the load you were hauling was mostly gear or mostly consumables.

Gear complexity is the opposite of simplicity and refers to the number of bits and pieces carried, as well as how hard they are to use. Complex gear increases your mental burden and usually is less reliable. Yet some people enjoy using complicated gear and nuanced skills for their elaborate setups.

The distance hiked per day is usually tied to other goals. Most backpackers reaching for bigger objectives such as thru-hikes also need to travel farther each day on average.

Beginning backpackers often aim for the best weather; as they build skills and refine their gear, they can take on more challenging weather. By the time someone reaches Stage 5, they often avoid trips in the most severe weather so they can keep their pack weight as low as possible.

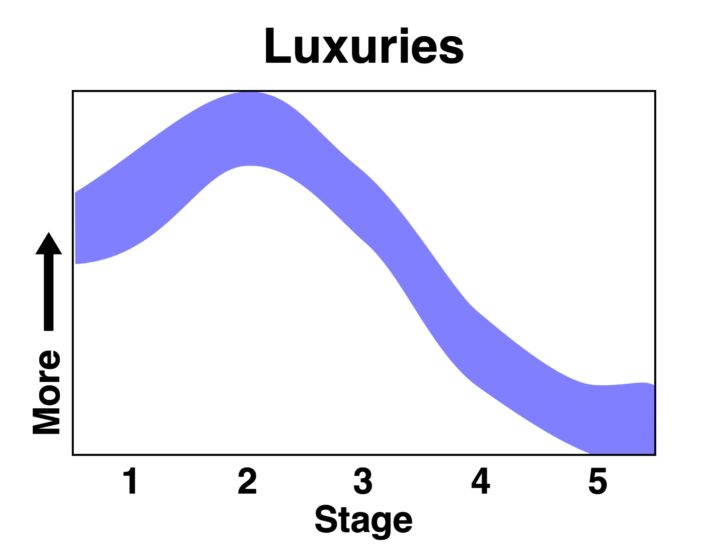

Luxuries are in the eye of the beholder. But our gaze often changes as we move to higher stages. Many who exit at Stage 3 or higher add back selected luxuries in pursuit of other goals. Some add luxuries hoping to reduce suffering, but that often backfires.

How much you suffer while backpacking is very subjective. Tolerance for suffering varies tremendously between people and over time. Plus, some people choose to suffer more in pursuit of bigger goals. But this arc seems to reflect many people’s journeys.

Conclusion

Not everyone will go through exactly these stages and arcs exactly this way. But what I’ve described seems to be a common experience, based on decades of reading stories, forums, and trail journals.

Again, you don’t need to aspire to a higher stage. Many backpackers are happy enough at Stage 1 or 2. Almost no one can jump straight to Stage 5 without years of focused skill-building and experience. Most people need to go through the earlier stages to gain a real appreciation for the later stages.

You might choose to blend pieces of several stages or arcs to HYOH (Hike Your Own Hike). Some of us step off this treadmill after realizing that fewer grams are not everything and that good enough gear is just that.

Related Content

- Rex writes about the hedonic treadmill of buying new gear – and how to get off that treadmill – in his piece Buy Less, Do More With Good Enough Gear

- In part of this wide-ranging interview, Michael Glavin shares his thoughts on the gear sweet spots.

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

- Product mentions in this article are made by the author with no compensation in return. In addition, Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for product mentions or placements in editorial coverage. Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light's gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you'd really like to support our work, don't buy gear you don't need - support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead. Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear.

Home › Forums › The Backpacker’s Journey