Introduction

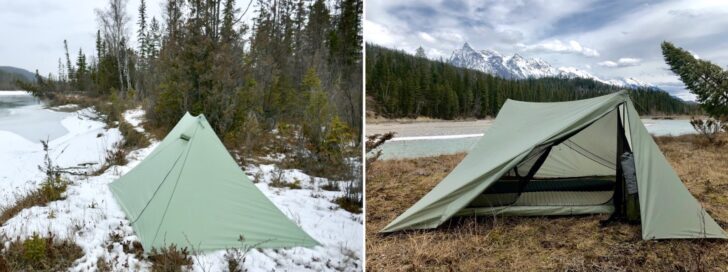

Dan Durston should be well-known to most Backpacking Light readers. Besides contributing articles and many forum posts, he worked with Drop.com (formerly MassDrop) to create the lightweight X-Mid 1P and X-Mid 2P tents, based on his original designs. Dan’s day job is as a fisheries biologist studying how the sediments suspended in rivers and streams impact the creatures living there. He lives, works, and designs gear in the small town of Golden, British Columbia.

We chatted for nearly two hours in January 2021, on many topics. This article focuses on standards and testing. A future article will cover tent design and the business of making and selling tents. I edited the interview for length and clarity.

A Great Place to Live, Work, and Play

Rex: I don’t know the small towns in B.C. Tell me more.

Dan: I’m in the best one. [From the east] go over the Rockies, there’s a valley, which is where I live. It’s a 10-kilometer-wide or 5-mile-wide valley, and then another 100 miles (160 km) of mountains. I moved here because the Rockies are world-class, and the Canadian Rockies are my favorite.

In any direction there is backpacking and skiing, and all the biggest national parks are around here. It’s great when you live somewhere awesome, and you have a lifetime of adventure right in your backyard. I spent a bunch of years on the coast, so I’m less wet now than I used to be.

People online don’t appreciate how areas can be different. They think everywhere is like where they are, and if you get condensation, you’re doing it wrong. And then people in the Pacific Northwest are like, how are you guys surviving in your little tiny single walls?

Standards and Design

Rex: What were some of the standards that drove your tent designs?

Dan: The waterproofness standard is important. It also really showed its limitations.

My two requirements for a good standard are that it represents how things are in the field, and it’s understandable. Waterproofness is very understandable – it’s a water column test.

But in terms of relating to the field, degradation is such a huge issue for almost all fabrics. We had PU (polyurethane) coatings 5, 10, 20 years ago that degraded pretty fast. People buy a 3,000-millimeter hydraulic head (HH) tent and then two years later it’s not waterproof. Then they say I need a 5,000. And then the 5,000 lets them down, they go for 10,000. It’s a durability or longevity problem, not an initial HH problem.

I like DCF (Dyneema Composite Fabric), but companies are hyping it up, like 8,000 mm HH, which is true. But it forms pinholes and micro-cracks. I wouldn’t trust it over a 2,000 mm woven [fabric] two years down the road.

For the X-Mid we wear-tested the fabric with Richard Nisley. He did all his tests, and HH over time. We were fortunate to find a fabric right away that held up really well. As a percent reduction, it was about as good as he’s ever tested.

Rex: The rainfly, with raindrops bouncing off taut fabric, has a very different waterproofness requirement from the floor, where you might be kneeling on wet ground for a long time. Can you discuss some of the differences with hydraulic head?

Dan: Certainly, there are differences. I take a new fabric and I can kneel on it, and see if it leaks. I can get that initial performance empirically, and then my main focus is how does this hold up over time?

That’s what I worry about the most, is how is this material in 5 years? And I don’t have a magic bullet answer to that. But that is why I’m such a fan of PEU (polyether urethane) over PU (polyurethane) because it’s going to hold up better. Silicone is great, too, but you can’t seam tape it, and those floors are just annoyingly slippery.

It’s hard to know what aging is because it’s so multi-faceted, but I’m basically doing anything I can to be less vulnerable to it with the coatings and the fabrics. And it seems like I’m starting with a good buffer. I think that we’re on a good trajectory.

We’ve never had someone say “my X-Mid leaks.” I’m surprised because we have over 10,000 out there now.

A Realistic “Aged HH” Standard Won’t Be Easy

Dan: [Saying we have 2,500 mm HH] leaves us at a competitive disadvantage because other companies say 3,500 and customers think they are more waterproof. But I do what we do because it represents how it really is in the field. I would benefit from an aged waterproofness standard. Then I could say “aged HH” is this.

That is the single biggest thing that’s missing, because that is a real issue with tents. How is the waterproofness 5 or 10 years down the road? And there is not much effort to address that.

Rex: I had so many of the early PU coated nylon tents basically rot on me. It wasn’t because I was putting them away wet. It was almost impossible to dry them out completely.

Dan: People think their tent is dry, but there is moisture inside, and that’s compounded by nylon because not only is the PU coating doing that, but the fiber is doing that too.

Richard’s test is a tumbling test, which would have basically no UV (ultraviolet) exposure. So even there, you’re missing something.

Standards Versus Simple Tests

Rex: Have you been involved in any standards committees?

Dan: No. Maybe the perspective I can provide is from the opposite end, where I’m pretty new to this. It’s hard because you have to pay money for the standard, and there’s a few. And you don’t know which one you want. Then you buy the standard, and it’s this really specific test where I’ve got to buy this crazy machine, or I can’t even do it.

What I end up doing is a lot of relative testing, where I’m not using a standard. Maybe I want to see how well two tensioners hold the cord. I’ll just put them on a bucket, fill it with water, and [figure out] this one is better.

I would prefer it if I was meeting a standard, where I could be publishing the results. But actually getting to that level is so much more involved in terms of equipment and precision. A lot of it, I don’t see that much value in, other than marketing.

Fit My Tent

Rex: There is this new website called Fit My Tent. What role that is playing in your marketing?

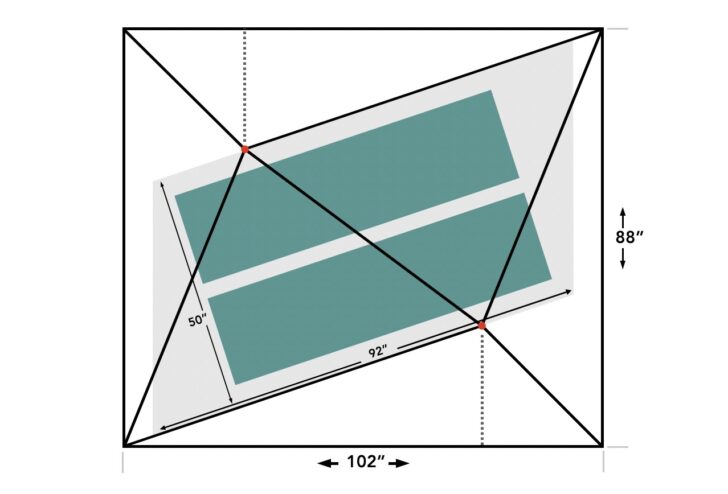

Dan: I have talked to the guy that’s doing it quite a bit, and that has illuminated how hard it is to simplify things. For example, the X-Mid has a diagonal ridgeline. You can measure it [straight across the tent] and it doesn’t look like that much, or along the diagonal where it’s a lot.

Tent fitting is really complicated to distill down. He’s using a 12-inch (30 cm) and 36-inch (91 cm) off the ground [length measurement]. I’m fine with the 12. I think that does a good job [at] getting at usable length. The 36 is a bit trickier because a lot of tents are right about that height.

Editor’s note: Measuring a set up tent at 12 in (30 cm) above the ground better reflects a sleeper’s needs than simple floor dimensions because that includes room for their head, feet, pad, and sleeping bag. And since most people’s sitting height is about half their standing height, measuring a tent 36 in (91 cm) off the ground can help with estimating headroom.

I personally think a 24-inch (61 cm) measure adds a lot, because 36 is so sensitive. But for just how much space is in my tent, I feel like 24 gets at that the best.

Rex: About shoulder height while sitting.

Dan: I’m also not confident it’s going to catch on even though it’s worthwhile. It’s hard to distill down to these metrics. They’re simplifications, but you also lose a fair bit in that simplification.

I see a widespread problem of accurate measuring. Everybody wants their tents to look good, so you’re going to measure it in a way that is charitable to the product, even if users might not get full space out of the product.

With the X-Mid 2P we made it 52 inches (132 cm) wide, and we marketed it at 50 inches (127 cm) because that’s what I think it is in the real world with some wrinkles. But then everybody else makes theirs 50 and it’s really 48 (122 cm). And then it’s 2% lighter and cheaper to produce.

I don’t know what the solution is.

Measuring Standard Tent Volumes

Dan: I personally like volume better. I know that tents have unusable volume, but it’s not actually that many cubic inches (cubic cm). Think about a single-pole [pyramid tent]. Those low areas around the outside, you trim all that off, maybe it’s 10% of the volume.

It’s simple, [customers] can see that this tent has 30% more volume than that tent, and it’s going to feel larger.

If people measure different ways, then it’s not going to work, like somebody’s doing fly volume and someone else is doing inner volume. If I pitch the fly tight, it is going to have more volume than if all the walls are sagging in. And similarly, a lot of floors are technically 50 inches (127 cm) wide, but only if they’re perfectly tight and wrinkle-free. If you grab an average 50-inch tent it’s probably about 48 (122 cm).

I agree there is a problem. I’m just not sure there is a solution yet that’s elegant enough to really catch on.

A Tear Strength Arms Race

Dan: With abrasion and with tear strength, I do my own testing. I have competitor’s fabrics and I know what a good fabric is.

Rex: At some point, you know that whatever you are doing is good enough, and whether it’s the highest tear strength doesn’t matter. And that gets lost in online discussions.

Dan: I totally agree, and I think that’s one of the problems. If tear strength was something that everybody published, it would just become this arms race. You don’t necessarily get any benefit in the field.

Weight Standards Not That Important

Dan: On weight standards, I don’t see those as important as some of the other ones. Customers right now can figure it out pretty much. Somebody counts stakes, somebody doesn’t, but it’s not as consequential as “I don’t fit in that tent” or “that tent leaks.”

Even when you say “trail weight,” people don’t know what that means. I just give an itemized list: fly, inner, you need four stakes, we give you eight, and they weigh this much. Obviously, we have to have a headline number, and we do the weight of the actual tent body without stakes. It’s a bit unrealistic, but it’s what so many other companies do. And fully disclosed in the specs for anyone that cares.

“I Hope You Don’t Use Fire Retardants”

Dan: The other contentious one is fire retardants. I get way more customers worried about the carcinogenic aspect of them. I’ve never had somebody say, “I really hope you have a fire retardant on this.” Whereas I get an email once a month saying, “I hope you don’t.” It seems like they are pretty unhealthy, so we don’t use them. We save a little weight by keeping it off.

Rex: And you’re keeping poisons out of the environment.

Dan: I’ve been trying to do more of that. It’s hard because I don’t have full control over a lot of stuff.

Just Three Product Testers

Rex: Besides yourself, do you use other product testers and how does that fit into your design process?

Dan: I have a friend, and my wife hikes a lot and she uses [my products]. To date, everything I’ve done has been a fast and streamlined process. But we don’t have a bunch of extra samples to send out to a crew of people who are going to use it for a couple of months.

Generally, when I get a prototype, it’s only two or three weeks until I’m ready for the next one. I’ll obsess over it and dwell on those thoughts for a bit and then, give me the next one.

With the pack, Drop did have a big field-testing program. They sent it out to 20 people. And they sent some tents out, too. That was their call. I didn’t think it was that helpful because [the testers] weren’t really the target audience, not lightweight backpackers. I think it’s only helpful to the extent that your testers are really knowledgeable.

Rex: At least for the market that you’re targeting.

Dan: I totally see the value. We probably would have caught that compatibility issue with the trekking poles if it wasn’t just three [testers]. If we had 40 people, somebody would have that style of tip. That’s part of the process of moving from this small nimble operation to a more mature operation.

But I’m also so picky that I have a hard time with other people’s opinions. It’s rare that somebody would have put more thought into an aspect than I have, like where the door toggles are, or should I move this up and down an inch (2.5 cm).

Conclusion

Rather than getting lost in a blizzard of expensive and confusing standards documents, followed by costly tests of dubious real-world value, Dan mostly chose quick and simple comparative tests to hone his designs. After selling more than 10,000 well-reviewed tents, that approach seems to have paid off.

In a later interview, we’ll chat about tent design, the business of making and selling tents, customer support, backpack design, and Dan’s future gear plans.

More Information

- Dan posts detailed information about his tents and backpack at https://durstongear.com, along with extensive notes on tent design philosophy and materials. Highly recommended.

- You can find Dan’s blog here, along with his guide to Stein Valley Nlaka’pamux Heritage Park, a provincial park in southwestern British Columbia, Canada.

Related Content

- More by Rex Sanders

- Check out our review of Dan’s pack. It’s an interesting read that illustrates how gear design can change during the prototyping phase.

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

- Product mentions in this article are made by the author with no compensation in return. In addition, Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for product mentions or placements in editorial coverage. Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light's gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you'd really like to support our work, don't buy gear you don't need - support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead. Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear.

Home › Forums › Standards Watch: Dan Durston Chats About Standards and Testing