Series Notes

This is Part 1 of 2 of the series Traversing the Elusive Nahanni River. Read Part 2 here.

Introduction

“What are you doing in August?” Michael texts me in January 2019.

Though I usually have my life arranged in advance, I’m never organized more than six months prior.

“Nothing I know of yet,” I text back.

“Good, do you think you can get a few weeks off?” Michael asks.

“I can try,” I reply, still not knowing what he had in mind. Michael wanted to paddle the Nahanni River in the Northwest Territories (NT). I wasn’t going to pass this opportunity up for anything. Within a month, I arrange my schedule to accommodate being gone for most of August of 2019.

My Attachment to the North

The Nahanni has a half-romantic and half-haunting allure. The area is probably one of the few truly wild places left in the world. In summer, it’s unpredictable, harsh, unforgiving, and remote. In winter, it’s only inhabitable by the fiercest and hardiest of any species.

I have been inching my way towards the far North for much of my life. Perhaps the first time I knew I would see the North was as a small child. As I sat on my Grandpa’s knee, he recited the Cremation of Sam McGee by Robert W. Service:

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge

I cremated Sam McGee.

Wonder, macabre curiosity, and an unquenchable wanderlust for the North filled my heart. I can still recite the entirety of a haunting poem that I memorized two decades ago.

My love of the North did not stop with Grandpa and Robert Service, though. It continued through reading every story Jack London wrote (a dozen times or more), and finally to the mystic Nahanni. Nahanni National Park Reserve holds the same kind of unearthly curiosity for me as an adult, as Sam McGee held for me as a child.

“The Cirque of the Unclimbables granite spires rise out of the lush alpine meadow, at Náįlįcho (Virginia Falls) the South Nahanni River surges over a drop twice the height of Niagara Falls. Nahanni National Park Reserve, encompassing 30,000 square kilometers, is a designated UNESCO world heritage site. The Dehcho First Nations welcome adventurers to Nahʔą Dehé, land of peaks, plateaus, and wild rivers.” Parks Canada boasted. I highly doubted it was an idle boast, either.

Developing Skills

In the back of my mind, my nerves frayed. I’m a backpacker who has paddled. I paddle well enough, but this was the outside edge of my skill. I am reaching, but I’m always reaching for the edge of possibility. This trip is the challenge I’ve been craving.

I know I need to adapt and adjust the lightweight backpacking theory to a different application. Canoeing is a different game; I know enough about it to realize I need to be flexible while still leveraging my skills. For leverage, I primarily require my ability to learn and adapt.

Risk Assessment

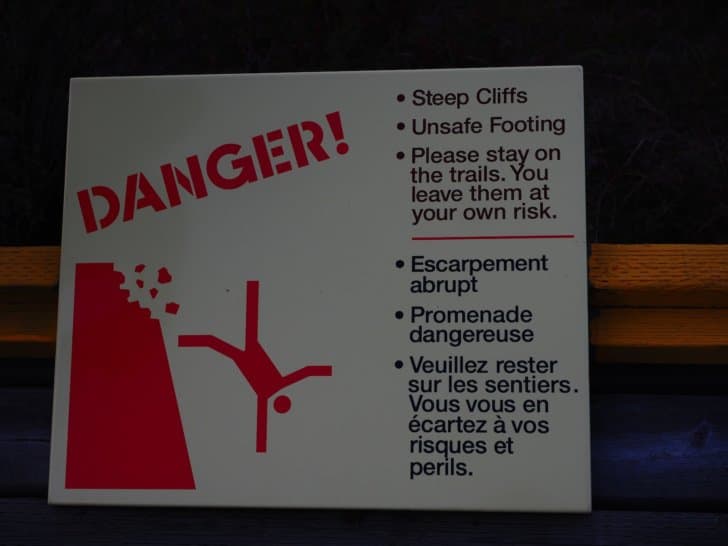

Nahanni is a massive river and by far the most prominent and fastest-moving river I have ever challenged. I could disappear into it without a trace. I’m not fond of the idea of becoming a statistic. Moreover, my biggest fear (after falling) is drowning.

Whitewater canoeing, unlike backpacking, isn’t always better to be ultralight. A canoe needs a ballast against rapids, waves, and wind, but lighter is easier to maneuver quickly. The ballast needs to fit into heavy dry bags and barrels and be lashed in with rope and carabiners. My skills in packing smaller and lighter will help, but almost two weeks of gear, food, backpacking, and camera equipment are dense and space consuming. If I have to swim or walk myself to help or safety, my ultralight backpacking will be an advantage. However, on the Nahanni, ultralighting will do next to nothing to mitigate rapids, strong currents, driving rains, or buffeting winds.

The remote and difficult to access area drastically restricts margin of error, I could be in trouble for over a week before anyone notices I’m missing. On many trips, it’s a day’s walk to the nearest highway or contact for help. In the Northwest Territories, it could be days or even weeks before aid reaches me and longer if I have to reach support myself.

No discussion of potential risks is complete without mentioning the potential of sharing space with various bears, ungulates, and birds. I recently obtained a telephoto lens, and I’m interested in close-ups of anything the Northwest Territories offers, but from a healthy and respectful distance of course.

At least, I had considered a worst-case scenario and knew what I was getting myself into…. Well, mostly.

Logistics

A trip of this magnitude has logistics. To complete the Nahanni, we need the following:

- Two proficient paddlers

- An appropriate canoe

- Gear of sufficient quality and quantity

- Massive amounts of food

- Extensive transportation

- Planning

- Training

Paddlers

Michael, a swift-water rescue technician and a paramedic, has spent more time in a kayak or canoe on whitewater than the average river rat.

I know how to paddle and I am a proficient swimmer. I’ve spent a good deal of time paddling, surfing, and swimming, but have barely touched a paddle since an accident back in 2015. My upper body suffered significant trauma. My recovery, though remarkable, has been slow. According to my physical therapy team, I owe much of my recovery to my fitness level, dogged determination, positive attitude towards a new normal, and continuously challenging limitations.

The same hyper-mobility, which saved my life in 2015, became my mechanism of injury in 2016. I had the displeasure of dislocating a knee that further slowed my recovery. Having since recovered to about 85% – 90%, I continue to push boundaries.

If nothing else, I know how to pick a gifted teammate. On a river, though, the team is only as strong as its weakest link. I (at 5’2 and 110 lb / 50 kg) am the weak link and have no illusions otherwise.

Canoe

The Nahanni is a big whitewater river. From Virginia Falls to just past Nahanni Butte, we’ll paddle about 150 miles (240 km), which drops a staggering 1300 feet (400 meters) over the course; not just any canoe is right for this type of endeavor.

I left the expert canoe selection up to Michael; he’s been researching the whitewater expedition member of his fleet for some time. He selects the Nova Craft Canoe Prospector 17 and orders a new one through the local retailer. He chose this canoe for its excellent primary and secondary stability and load capacity for long trips.

Specifications

- Material: SP3: 99 lb (44.9 kg)

- Length: 17′ (518 cm)

- Width: 36″ (91.4 cm)

- Center Depth: 15″ (38.1 cm)

- End Depth: 23″ (58.4 cm)

- Rocker: 2.5″ (6.4 cm)

- Capacity: 1200 lb (545 kg)

Features

- Symmetrical Hull

- Shallow Arch Bottom

- Moderate Rocker

- Available with or without shoe keel in some materials. Weights listed above are for no-keel versions.

There are lighter but less durable and more expensive options out there. As this canoe will also be used on shallower whitewater, the more durable and substantial option is better. Nothing would be worse than being up the Nahanni without a canoe.

Gear

For Nahanni, my standard backpacking gear still applies. Additional equipment also needs to be added. Considerations include barrels, Pelican boxes, dry bags, wet suits, dry suits, paddles, neoprene socks, spray decks, neoprene booties, paddling gloves, neoprene gloves, PFDs, river knives, rescue gear, water safety kits and other equipment native to water travel. Fortunately, I have much of the gear tucked away in a box in the back of my closet. If I don’t have it, Michael still does. We both upgrade some equipment, but our inventories remain mostly unchanged.

Food

As we plan and pack food for the trip, I am not behind the eight-ball. Planning meals and making food tasty, compact, quick, and lightweight is one of my specialties. I’m also a master of collecting backpacking food from a grocery store when it’s on sale to keep costs down.

Michael rolls with my Excel spreadsheets and grocery lists. He is not inclined to complain about meals like Hawaiian pizza, tacos, chili cheese mac, garlic cheese biscuits and gravy, vanilla cake with icing, and banana cream pie.

He also doesn’t seem to mind my versions of backpacking meals that are tailored to taste and cost significantly less than commercial backpacking meals. On average, homemade meals weigh the same (sometimes a bit more, give or take) as commercial ones. They also have significantly less sodium and preservatives. Packing meals as a team reduces space and packaging requirements. With the inevitability of spending hours or days in the rain (or swimming), we opt for more warm meals than cold. Fuel reduction is natural as Nahanni permits campfires.

Transportation

Though I am in Canada, getting to Nahanni National Park Reserve is more complicated, dangerous, and time-consuming than flying to New Zealand. With about 1060 miles (1700 km), over 24 hours of driving time (one-way), and a chartered bush plane, planning Nahanni is not for the faint of heart.

The Reserve itself requires travelers to obtain a permit and register at Fort Simpson before continuing to Lindberg’s Landing. At Lindberg’s, we meet the bush plane pilot before flying into Virginia Falls and starting the adventure in earnest. Once returning to Lindberg’s Landing, by paddle or foot, over a week later, travelers must return to Fort Simpson and unregister the permit. Fortunately, in actual practice, the Parks Canada office allows phone registration and deregistration if we have a phone service (which is unlikely.)

To fly into Yellowknife, NT from Edmonton, AB (a two hour, one-way flight) is $250 – $900 CAD per person, in economy seats, without any equipment besides what could fit in a carryon. From Yellowknife, a traveler has to make it to Fort Simpson or Lindberg’s Landing. It is possible to charter a guided tour to save some logistics, but it also comes at a high cost ($5,000 – $10,000 CAD.)

Michael volunteers to handle the permits and bush plane bookings (I will not argue), and we split the driving time and cram (us and gear) into the truck for well over 24 hours.

Training

If nothing else, I have confidence in my swimming ability; though I am not confident about how I feel about rivers. Lakes, oceans, and rivers are distinctly different beasts. I’m confident on the lake, competent on the ocean, but nervous on a river. I’ve been on rivers before and found them pushy and unforgiving. Somehow though, I am compelled to go to rivers every few years. I never have the heart to let go of all my river gear.

In spite of my fear, I’ve always had an affinity for water. When I went to Mexico to snorkel, dive, surf, and paddle, locals kept calling me “la Serena,” or “the mermaid.”

On the other hand, drowning is one of the highest causes of death for outdoor people (after falls.) Nothing is so firmly fixed in my mind as the thought of me drowning. After falling, drowning is my greatest fear.

That said, here I am, up a river with a paddle, a PFD, and questioning my sanity. The only way to mitigate my risk, gain competence and confidence is to paddle. Michael’s big plan is to let me paddle every river between Alberta and NT as soon as they melt and until August. Fortunately, I have almost everything I need already:

- Wetsuits

- Helmet

- PFD

- Kayaking odds and ends

North Saskatchewan River

Finally, one early morning in June, it’s time to test my mettle, and get my first whitewater canoeing lesson. The paddle feels like a shoe on the wrong foot. It’s too short compared to sea kayak-paddle. Everything feels awkward and clumsy; mostly, I am a bundle of nerves.

This first trip out is an acid test. After my accident a few years ago, I scaled back my activities. I found ultralight backpacking and all but abandoned kayaking. I don’t know if my shoulders and spine can withstand paddling again. Compounding my concern, when I get nervous, my joints ache from my previous injuries. I tense them and hold my rib cage like it’s still broken.

Shuttling

On the drive out to the canoe launch point, I blast my stereo and try not to think about it. I am meeting Michael at Preacher’s Point in Kootenay Plains, Alberta. I’ll leave my vehicle at the canoe take out on the North Saskatchewan River.

I park my car, and Michael pulls in behind me. I hop into his truck, and we continue down the mountain highway to the canoe launch near Saskatchewan River Crossing, Alberta.

Michael notices I am nervous. “I can paddle this one solo; you don’t have to paddle at all if you don’t want to,” he says. Which in my mind, voids the point of the activity.

I grin and laugh, and say “If nothing else, I’ll make almost useless ballast in the bow.”

Route

He covers the route details on the drive. The river runs about 56 km and is a braided channel most of the way. There is a risk of log jams along the entire route.

As Micheal ties in our gear, he covers basic safety:

- Don’t risk yourself for saving your equipment. You’ll probably find it quickly downstream. Otherwise, it’s tied in and will stay with the canoe even if it’s upside down.

- Stay with the canoe unless you need to swim to avoid a hazard.

- Hold onto your paddle if you can. A paddle makes safety equipment to help you catch an eddy, get to shore, or avoid a hazard. Let go of the paddle if it becomes a hazard.

- If you swim, always keep your feet pointed downstream with toes and nose facing sky side.

- Swim diagonal to the current, avoiding hazards. Try to reach an eddy or shore as safely and quickly as possible, but don’t exhaust yourself doing it.

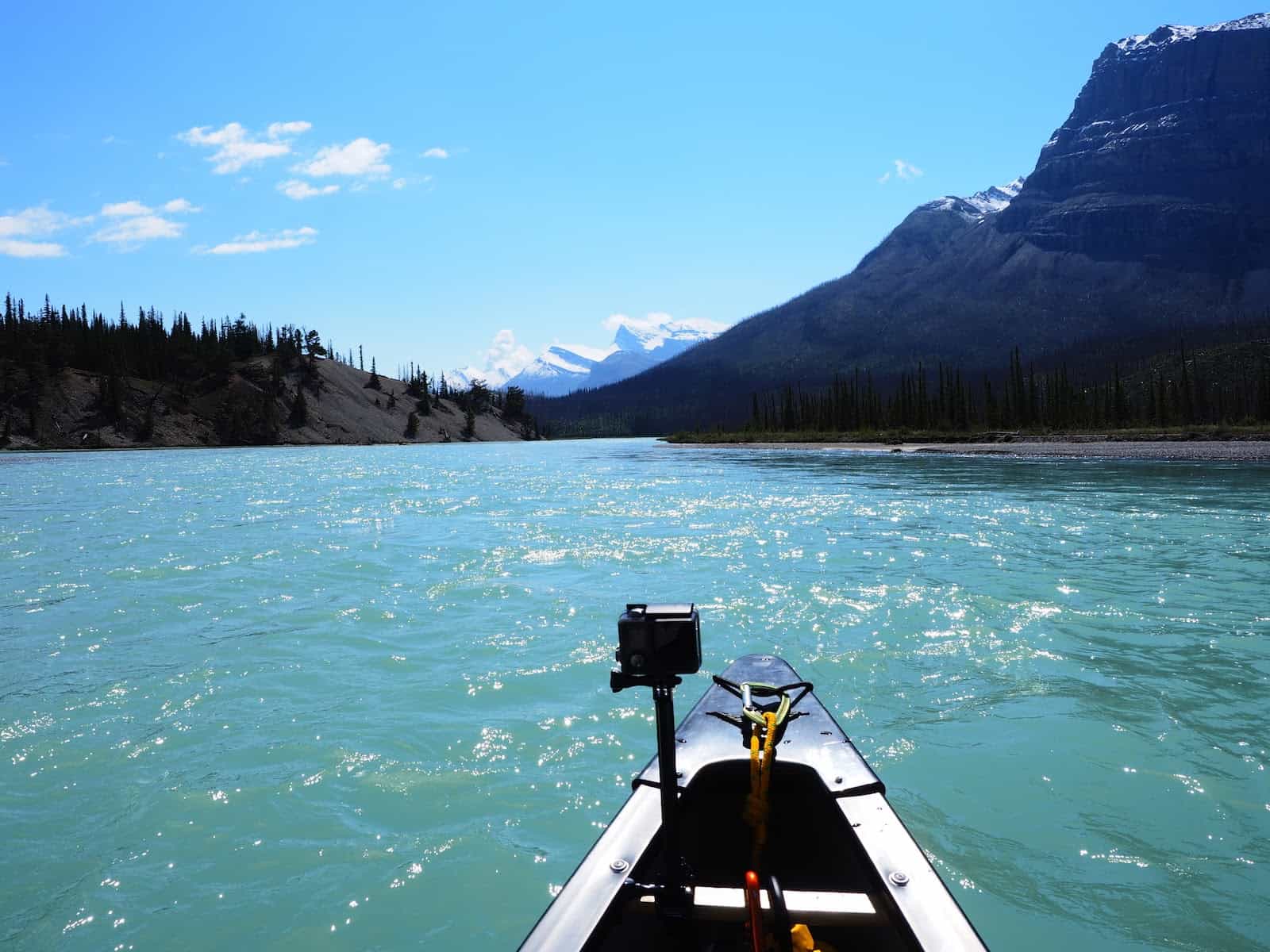

Finally, Michael pops a GoPro in front of my seat and tells me that my job is to get the footage. I internally grimace, as any nervousness on my face will have a front center view. I hide behind lenses to avoid being in front of them.

The North Sask is not a beginner route without someone who could paddle it alone. Although it has good examples of river features, hence it’s a perfect training ground for a rookie with a coach. This section is much smaller than Nahanni, and as we push off from shore, I further question my sanity.

Paddle

I clench my jaw and my paddle. No one has talked me out of whitewater in years. I’ve known people who have drowned or almost drowned. I’ve thought about drowning once or twice myself. Near drowning, in my experience, involves panic, cold chills, agonizing cramps, and an abiding fear of drowning.

Sitting in the bow on the North Sask, I know I’m a figurehead. A wind-torn siren, decorative but without purpose. Nahanni, though, will take teamwork and both paddlers’ strength to navigate. Without a glance backward, I test my paddle while Michael starts coaching on my technique.

He talks me through maneuvers, and the current repeatedly rips at my paddle while I follow instructions. The river splashes and howls past rocks and logs, forcing us down its course.

As I ease back into whitewater, I slowly recall how to catch current lines properly. As I relax, I glance at the scenery all around us.

Everywhere around the river, the vetch, fireweed, primroses, and prairie fire are in full bloom. The mountain air pours into my lungs and infuses my hair with subtle aromas.

I can hear the river singing all around me; sometimes its voice so loud, I can’t hear Michael’s instructions, so I paddle by instinct.

It’s breathtaking. While sitting in the warm sunlight, I remember why the rivers call me back year after year.

Several hours of paddling later, we pull into Preacher’s Point. By Michael’s estimation, I’m a rusty, but easygoing and natural paddler. By my estimation, my shoulders and abs ache from the current ripping at my paddle.

One river down; as many as possible to go between then and August.

Our Trial Run

After months of prep, two weeks before Nahanni, Michael and I decided to make one last multi-day test run. To my chagrin, I am negotiating contracts and barely ever available for packing (aside from dropping my gear and lists off and occasionally providing input.) Between my lists, Excel spreadsheets, and his expertise, Michael packs almost everything without me.

For readers who have read my trip planning article, you will recognize the extraordinary amount of trust and self-control it takes to allow someone else to plan and pack for me. Though I have pre-planned for Nahanni, this trip is impromptu, and it’s testing my adaptability.

The fact that I am handing Michael the reins indicates to me that my trip mate is reliable. I’ve said before, trusting and liking your trip mates is critical.

If you catastrophically disagree with a backpacking partner, then likely the worst which happens is you walk home alone (possibly with hypothermia or a minor injury.) Though you can end up dead backpacking, there is usually a wide margin of error and opportunities to correct course. In paddling or climbing, though, a disagreement between trip mates could lead to a significant fall, a swim, an injury, and, at worst, death. Nahanni has critical elements for things to go badly wrong: remote access, open fast-flowing water, and high cliffs.

North Sask, Round Two

The smell of bacon and coffee woke me up around 6 AM on a Saturday morning. Without knowing exactly what was packed, I follow Michael back out to another section of the North Saskatchewan River. This time it would be three days out on the river, and there would be hazards, training, rapids, and gear trials.

My last practice run down the North Sask started at Highway 93 Crossing in Jasper, Alberta, and ended west of Lake Abraham (colloquially known as Lake Abe.) This trip begins downstream and east of the Lake Abe Dam.

After all the practice sessions, I’m not nervous. Instead, I’m anticipating fun and a much-needed escape. Once most of the gear is organized, packed, and loaded, it’s almost midnight, and I tumble into bed.

Day 1 – 22 Miles (35 km)

Launch

Early Saturday morning, I drag myself out of bed for a quick coffee before driving to the Lake Abe Dam. We arrange for someone to shuttle the truck to the takeout after we drop off our gear at the launch point.

Once we arrive downstream of the Lake Abraham Dam, we start organizing logistics; loading gear, tying in and finally climbing into our neoprene suits.

Paddle

The first section of the North Saskatchewan River we are heading into is generally not recommended for novice or nervous intermediate-paddlers. At first, though, the river seems safe with a slow-moving, almost lake-like surface. Not far in though, it takes a turn for the worse with dangerous strainers and log jams which have ambushed more than a few unwary paddlers.

Fortunately, Michael is neither unwary nor cocky about this section of the river. From being part of rescue teams, he knows this section of the river well.

On the River

In a short while, what appears as simple lake-paddling becomes a braided group of channels with log jams, sweepers, and strainers around each bend.

My heart is pounding most of the day as we scan around for hazards, and frequently encounter them. I barely remember to take photos as we dodge massive log jams. We pull off on scouting missions and quick breaks throughout the day. As Michael promised, we bypass the hazards with ease.

Now, through the riskiest section of the river, and with what looks like a soaking rain coming in, we decide to camp for the night at about 3:30 PM.

In Camp

We set camp and get a fire started and a tarp up just in time for a heavy afternoon shower. From my perch on top of a barrel, I watch as my little campfire valiantly resists the rain, and with a bit of help, stays just hot enough to survive almost 40 minutes of soaking rain.

Dinner consists of Tunagetti, a meal test for Nahanni. It’s good with its sundried tomatoes, garlic, salt, pepper, olive oil, Parmesan cheese, tuna, and stir fry noodles. It’s also, thankfully, warm. Though we didn’t go for a swim today, the rain certainly adds a chill.

Day 2 – 39 Miles (63 km)

On the River

Michael and I slowly develop a morning system. He is tall and more of a morning person than I am. Packing up the sleeping gear in a tent during the rain is more or less the bane of his existence. I am not a morning person (without caffeine.) At 5’2, I can easily pack up equipment inside a tent.

Michael opts to be in charge of starting the coffee and the morning fire. I pack up the sleeping gear and join him for coffee shortly after that. The rain slowly dissipates. We finish packing everything into barrels and loading the canoe before donning neoprene.

Back on the river, it’s desolate. We have only seen one other group. Usually, this river is relatively busy, but we theorize the current flood conditions scare most paddlers off.

I realize that I find paddling relatively untechnical, especially after yesterday. As Michael points out, flood conditions don’t necessarily equate to a more dangerous river. Flood conditions can erase rapids and safely bury obstacles in the depths. Some of the most technical water in the world isn’t deep but in fact shallow, and the river bed has more impact on the course.

What flood conditions do dictate is a faster river. A faster river means if there are obstacles, you have to respond faster and have less margin for error. Nahanni is a quicker, bigger river. Not only will we have to respond faster, but we also have more distance to cover when we respond.

The Chase

As we paddle the river, it becomes increasingly apparent that a thunderstorm is chasing us. Yesterday we stopped to avoid the storms, but today we need to make miles. We have to make up for lost time or risk not making it back to Rocky Mountain House in time for looming responsibilities.

For hours we face the sun with our backs to a storm. We manage to stay just on its border and miss the worst of the rain before about 7:30 PM in the evening and pull into shore to camp.

In Camp

Our teamwork system further develops as Michael learns we forgot the fire-starting paper. He realizes I have better fire-starting skills than a troop of Boy Scouts and don’t need paper. After my valiant little fire stayed ablaze in a torrential downpour yesterday, Michael is happy to make me fire goddess for the duration.

We fall into another routine where I start the fire and start unpacking the kitchen, while Michael sets up shelters. We then switch. I begin assembling sleeping gear inside tents, and he finishes unpacking the kitchen and starts supper over my roaring fire.

I have a penchant for fire craft. I like building fire pits in all-terrain. On my native prairies (in any season), or in the boreal forest and near coastal waters, I can start a fire in a matter of minutes, sometimes even in spite of driving precipitation.

Though time is not on our side, daylight this far North of the equator is. We spend the remainder of the evening testing out Beef Stroganoff and drinking hot chocolate, while intermittently avoiding short mountain squalls and rain under a tarp.

The morning will come early. The last section of the river features a series of rapids, which includes the Devil’s Elbow and the Three Bears.

Day 3 – 19 Miles (31 km)

In the morning, we prepare for rapids and strap on the spray deck. Michael has decided I am sufficiently seaworthy to attempt rapids. We’ll catch the Devil’s Elbow, and a few others before we reach the truck in the afternoon. In a worst-case scenario, it’s a safe swim, and we should find the canoe washed up not too far downstream.

Fortunately, in spite of repeat attempts (on Michael’s part) to see if I know how to swim, we make it to Rocky Mountain House. Throughout the trip, we kept a log of things we forgot or didn’t think of, and in the remaining week will finish packing for Nahanni.

Packing Strategies

12 days of equipment and over 3000 km worth of supplies for driving and camping is not a small load or a short list. Every spare moment of July 2019 is dedicated to packing or testing equipment for Nahanni.

A Nahanni River trip is like planning the most remote possible 13-day thru-hike. A shoulder-season thru-hike, with no resupply, and the added requirements of whitewater canoe equipment.

Canoe Equipment

Whitewater canoe equipment includes: three 60 liter river barrels, one 30 liter river barrel, a 115-liter portage pack, two Ocoee Watershed dry bags, two Watershed stern bags, and one 20 liter Sealine drybag empty weigh more than all my backpacking equipment (in use and not) combined. A canoe (which we christened Kermit), a Northwater sprayskirt, four paddles, a pin kit, four throw bags, a bailing bucket, and a bailing sponge weigh more than Michael, and I do by far.

Additional canoe specific gear includes wetsuits, neoprene socks, neoprene gloves, paddling gloves, river shoes, PFD (personal floatation device), river hat, bathing suit, and quick dry tube scarf. An extra set of dry layers is required in case of a swim. Firestarter and stove are also not-optional.

Seeing the massive pile of equipment makes the ultralight backpacker in me want to break out in hives. However, trying to make a list shorter and shrink the collection proves to be almost impossible. Whitewater canoeing is different; it requires more and a different sort of equipment.

Camera Equipment

I am almost certain I will not return to Nahanni again. With that in mind, I pack my camera equipment in Pelican boxes. Ultralight backpacking has allowed me to pursue my passion for photography, and I’m not about to let whitewater prevent my pursuits.

Backpacking Equipment

Backpacking equipment is easy. I won’t ever need an overnight pack, but I will need a day pack for layers, food, hydration, safety equipment, and camera equipment on unmarked treks up the river canyons. A tiny 9-liter day pack with a hydration system will meet my needs adequately.

- Osprey Tempest 9L

- Platypus Hydration System

- The North Face Thermoball Insulated Jacket

- Outdoor Research Helium II Rain Jacket

- Outdoor Research Helium Rain Pants

- Minimalist first aid kit

- Lighter

- Ditty kit

Everything weighs well under 10 lb (4.5 kg) and takes up next to no space. Obviously, I also have basic camping things like:

However, at no point, except portaging, will I carry these items.

Food

Food on this trip challenges my creativity. The journey ahead is long and expensive. In total, I need about 16 days of supplies (including road days.) I am half famous for not eating my food if I’m tired and the food is boring, which is not ideal on a long duration trip. I rarely get to plan a menu with many options, especially not on one trip.

Fortunately, canoeing allows me liberty I rarely have. So, I’m bringing my Banks Fry-Bake Oven 12 oz (340 g.) I am also bringing a pot, a kettle, and my coffee press. This type of kitchen allows me to bake, boil, fry, and backcountry chef, to my heart’s content.

For a backpacking trip, I would have to pick one or two of these items at most; canoeing lets me have a full outdoor kitchen. This is only limited by space, and I have to creatively fit a large kitchen and an almost expedition amount of food in barrels. The food here sounds gourmet, and to be sure it is, especially since it is virtually all dry or powdered shelf-stable goods.

The dinner menu includes:

- 2 Tunagetti meals

- 1 Chili Cheese Mac meal

- 2 Garlic Cheese Biscuits and Gravy meals

- 2 Beef Stroganoff meals

- 2 Teriyaki Stir Fry meals

- 1 Hawaiian Pizza meal

- 2 Beef Burrito meals

Dessert includes:

- 1 Cake with icing

- 1 Apple Crisp

- 1 Chocolate Mousse

- 1 Vanilla Pudding

- 1 Lemon Pudding with whipping cream

- 1 Banana Cream Pie

- Hot chocolate

- Tea

- Lemonade

- Ice Tea

Lunches and snacks are a free-for-all with:

- 4 or 5 flavors of Protein/Granola bars

- 4 or 5 flavors of Chocolate bars

- Mixed unsalted nuts

- Chocolate covered coffee beans

- Dried fruit

- Swiss chocolate squares

- Wasabi peas

- Beef jerky

Breakfast includes:

- Bacon

- Eggs

- Hash Browns

- Pancakes

- Granola

- Coffee

The kitchen is the only place I severely depart from ultralight backpacking on this trip. However, If not for how light and compact the food is, I wouldn’t be able to pack half the cheffing equipment I’ve managed to fit in. Half of this trip is the freedom to depart from ultralight backpacking in the kitchen and test what I can accomplish with backcountry gourmet. Canoeing an extremely remote mountain river is the only time my kitchen supplies might be of value in a rescue scenario as well.

For the drive, I tuck in powdered soups, tortillas, fresh fruit, and a selection of other bits and bites which can’t survive packing into barrels.

Culmination

After eight months of planning and packing, leaving for the trip flows relatively seamlessly. Seeing the pile of gear disappearing into seaworthy containers and into the bed of the truck with a 17’ canoe overhead feels like a feat of engineering. It takes till almost midnight to complete packing. I stash the last item and collapse into bed.

On the Road: Big Sky and Seas of Green

As expected, the morning starts close to dawn. I stretch, and my mind starts sorting through all the things I may have forgotten. I grab a few last-minute items as I drink my coffee and eat my breakfast. Michael opts to drive till he is tired, then I will take over. We want to make it from Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, to at least High Level, Alberta, which is about halfway.

Day 1 – 652 Miles (1050 km)

Approximate Fuel Price:

- $4.40 CAD / $3.30 USD per gallon, $1.10 CAD / $0.83 USD per liter

The drive starts at 7:45 AM in the seas of green forests, fields, and hills of livestock. Slowly, forestry and grazing lands give way to seas of golden canola, wheat, oats, and barley. Hours pass with conversation and podcasts. Occasionally we stop for fuel or truck snacks before continuing ever North.

At 6:30 PM we arrive at High Level, Alberta, which is about 800 km from Lindberg’s Landing. Neither of us is ready to stop driving, and we want to shorten Tuesday’s driving time. After getting fuel and a bite to eat, we continue Northward, hoping to make it to the Northwest Territories border before nightfall.

Approximate Fuel Price:

- $4.00 CAD / $3.00 USD per gallon, $1.00 CAD / $0.75 USD per liter

As we drive, crop fields fade into the rearview as thick tangles of trees and undergrowth take their place. At 8:30 PM, we reach the 60th meridian and the Northwest Territories border. We covered 1050 km in a single day, and we both feel it.

Sadly, the visitor center is closed, but there are empty campsites. We set up camp and crawl into our beds for the night.

Approximate Park Fees:

- Campsite: $25

Day 2 – 365 Miles (588 km)

We allow sleep in till 7:30 AM before packing up and registering at the visitor center when it opens at 8:30 AM. The manager of the campsite is friendly and gives us information about the nearest fuel (Hay River, NT – an hour and a half and a 76 km detour, or Fort Providence, NT – 2.5 hours and a 50 mile (80 km detour) until we get to Lindberg’s Landing.

Hay River

We opt to stop at Hay River for one more fuel up. Aside from almost vacant Enterprise, we won’t see another community, house, or sign of civilization except for the road and the occasional vehicle.

Approximate Fuel Price:

- $4.80 CAD / $3.60 USD per gallon, $1.20 CAD / $0.90 USD per liter

Within hours, we leave the pavement and cell service behind for the next two weeks. As we travel, we notice how the amount of traffic dwindles. As we drive, we see one other vehicle every hour and a half on average.

Numerous pull-outs with trash disposal and the occasional outhouse make the drive North and West towards Fort Simpson and onto Lindberg’s Landing pleasant. As the hours pass, the complete isolation of Northern communities sets in. We are truly alone here, and the Nahanni National Park Reserve, though a focal point in the area, will be no less isolated.

The further we get down this highway, the more I crave the isolation. My life has often taken me far from my natural state of quiet solitude. The Northwest Territories feels like home in its reclusive independence.

Lindberg’s Landing

When we arrive at Lindberg’s Landing, we find that it’s obviously not ideal for camping or parking. There is a floatplane dock but no cell service to call the airport or the park. Our flight won’t arrive till 10 AM tomorrow (August 7) anyway.

Blackstone Territorial Park

Michael saw a sign for a Territorial Park, and instead of camping on the lawn at Lindberg’s, we opt to check the park. We have been impressed by parks in NT, and Blackstone Territorial Park is a gem. Fully staffed, coffee, and room for us to camp, park a vehicle for two weeks, a shower house, campsites on Liard River, and cell service have us sold on the park just a couple of miles from Lindberg’s.

Blackstone’s manager, Curt, tells us to pick any tent site and come pay him after. We choose a site right next to the river and hatch a plan to pay the parking fee for two weeks and paddle our gear downstream to Lindberg’s Landing in the morning.

Approximate Park Fees:

- Park access (if not purchasing overnight or facility permits): $5

- Shower House access (if not buying overnight or facility permits): $5

- Campsite (includes access and showers): $25

- Multiple week parking passes: $30

Day 3 – Delay

On August 7th, high winds, cloud cover, and rain convince us (and Simpson Air), flying to Virginia Falls is not an option first thing in the morning. A steady North wind blows, and lazy meandering North-flowing Liard River is white-capped and flowing South. Simpson Airlines has us call back every two hours for flight updates.

The locals keep us entertained as we wait for our flight:

Curt, who seems apologetic for our flight situation, starts a fire and coffee in the visitor center fireplace and makes us feel at home while letting us dry our gear. We watch high winds drive the Liard River’s southward current northwards for eight hours, and Simpson Airlines delays our flight till August 8th. Curt offers to rent us one of Blackstone’s cabins to keep us dry and more packable for the next day. He also offers to shuttle us to Lindberg’s after we drop our gear off by truck to avoid spending time paddling the Liard River in the morning.

A night in a cabin, keeping gear dry was a welcome relief. We knew we would eventually get soaked, but it was nice not to start there. We didn’t sleep well because of the storm and a few “unwelcome guests” (mice), but in the morning, we are dry.

Approximate Park Fees:

- Cabin Rental: $60

Day 4 – 101 Miles (162 km)

The weather still looks questionable, and we call Simpson Airlines. Simpson Airlines receives a “weather report” (there are no local weather stations) from a Parks Canada Officer at Virginia Falls at 9 AM. Our flight was delayed until the report came in. When we call at 9 AM, the flight is confirmed, and the pilot will arrive by 10:30 AM.

True to his word, Curt shuttles Michael back to Lindberg’s.

Ron tells us the weather over the Nahanni River is unpredictable and volatile today. Clouds are low over the passes, and Ron isn’t sure we can get through, but he’ll try.

My heart is in my throat as the plane takes off. Bush planes do not have the highest safety track record, but Ron seems professional and cautious.

Wild Blue Yonder

Once in the air, I am almost catatonic as I see the vast expanse of barren muskegs and mountain ranges. Behind each mountain range is another. The expanse does not end. There are no signs of humanity in any direction. It’s a harsh looking environment where only the hardiest of beasts survive and few if any, humans dare to venture.

One thing is crystal clear in my mind, I do not want to get lost in this wilderness. I might never be found, nor would I be likely to be able to locate help for hundreds of miles.

After almost two hours of searching for a clear pass, we exhaust the known routes for a Cessna to get into Virginia Falls.

I can see Ron is increasingly agitated and turns back without hesitation or further explanation. To be fair, I’m more nervous and more than ready to feel the firm ground beneath my feet.

The Gap

Ron decides to set the plane down at a nearby bush refueling station at Little Doctor Lake. Little Doctor Lake is one of the few places to safely set a plane down nearby. It’s also guarded by a ridge known as “the Gap.”

As Ron flies through the Gap, it looks like we could reach out and touch the sides. High winds blow through the Gap like a wind tunnel and shake the Cessna and its contents (me) like a Magic 8 Ball. It feels suddenly like an elevator floor drops out from under us. My fingernails embed into my seat as I tighten my grip, clench my jaw, and weld my eyes shut.

The turbulence rocks the Cessna, and I vow to give up flying, or chocolate, or whatever it takes to be safe on the ground:

Little “Doc” Lake

Pontoon waves ripple behind us, and the shore of Little Doctor Lake is a direct contradiction to the storm we left behind in the Gap. The air feels warm, and there is a hint of sunshine.

Another plane with four passengers on board is also grounded at Little Doc Lake. Both pilots opt to spend the afternoon with us waiting out the storm. Soon all hope of getting through to Virginia Falls is lost, and the pilots unload our gear from the planes and take off for Fort Simpson.

We (and our new friends) are stranded on the lakeshore till morning.

New Friends

As we sit on the beach, we make fast friends with some other Albertans (Bruce, Bruce, Donna, and June) who, like us, are enjoying the view at Little Doc Lake but are anxious to get to the Nahanni. Our new friends have been separated from the other half of their group too (Chris and Ken.)

Michael and I are starting to wonder if we can paddle fast enough to get him home to his job as a Paramedic. It’s unlikely his employer will understand about a flight being delayed for two days.

In this circumstance, we will hike around Virginia Falls tomorrow as soon as we get there. We estimate we should be at Virginia Falls around noon if Ron’s promise to see us “in the morning” pans out. We’ll have to forgo most of the other hikes because if we don’t, we might not make it back in time for Michael’s shift.

With our strategy planned, we get our tent set up and make Hawaiian pizza and white cake with icing. With two full days of delay, we also now have at least two extra days of food.

One of the Bruces has paddled Nahanni before and gives us ideas of where to camp and which hikes we should try to get in.

Day 5 – 46 Miles (74 km)

Delay Day

Morning arrives, and for the third day in a row, we eat breakfast, pack and await a plane. To our surprise and delight, the skies are clear, our plane has to arrive soon. 8 AM becomes 10 AM, and 10 AM becomes noon.

Michael is on edge. Usually, he is the more even-tempered of the two of us, and it’s throwing me off. He is afraid we’ll miss our deadline to get back, and he’ll miss work. For a medic, missing work would likely mean losing his job. We have no way of predicting weather conditions. We make a pact that we cannot stop anywhere on the river, and we have to paddle every day no matter what happens.

The afternoon wears on long enough so I take a dip in the lake. An hour later, I climb out of the lake, and there is still no sign of our plane. Overhead we can hear Twin Otters flying towards Virginia Falls, and we know flights are making it in. Michael and I seriously discuss abandoning the trip and having the pilot fly us back to Lindberg’s Landing instead. At 4:00 PM, we resolve to abandon the trip if we don’t make it to Virginia Falls tonight.

Virginia Falls

Ron feels terrible about how long our flight was delayed. To make up for it, he is giving me a direct flight over the top of the falls. He’s not supposed to fly over the falls, but he knows I am a photographer and is gifting me a photo from above. I have just one shot at this. I won’t have time to take a second one. My hands shake nervously as I screw on my precious telephoto lens and line up for the shot of my lifetime.

As I look at the falls, my heart is in my throat, but almost as soon as I glimpse them, they vanish into the calm, lake-like waters of the Nahanni River above the falls.

No Room in the Inn

As we land and start unloading, we are met by Parks Canada staff. We have no reservations, had no way to sign in with the Parks Canada staff, and our two overnight permits for Virginia Falls are expired.

Ron smooths things over, and the Parks Canada staff tell us there are no campsites; they’ll work something out and squeeze us somewhere. Just then, one of the Bruces comes off the dock and starts helping haul our gear up onto the shore. He and his crew have already saved us a tent spot with them. They have been waiting for us all day.

As soon as our gear is unloaded, we wave goodbye to Ron, and he takes off for Fort Simpson and home. We take our equipment into camp and have a reunion with our fellow castaways.

A View from the Top

We only have tonight and tomorrow morning to explore Nahanni, but we are also travel-worn. As soon as we have our tent and gear set up, we race to explore the falls before dark.

S’mores with Great Friends

Darkness comes, despite our wishes for a bit more time. Once it’s completely dark (and past midnight), we return to our tent site. Our new friends are still awake and have a beautiful campfire roaring.

Without the sun, there is a new and vengeful chill to the northern air. We all huddle in close to the fire, and Michael and I share one of our precious few pure luxuries: maple marshmallows and chocolate-covered cookies for s’mores. Our new friends have made all the difference tonight, and we are grateful for their help and company.

The evening becomes bittersweet as we realize, Bruce, Bruce, Donna, June, Chris, and Ken will not be joining us for the remainder of the trip. From here, Michael and I are completely alone.

Part 2

- Continue – read Part 2 here.

Home › Forums › Traversing the Nahanni River by Canoe (Expedition)