I’m Doing Fine!

Throughout the summer, despite the ongoing pandemic, an uncertain relationship, political division in the U.S., the impending election—and the possibility that it wouldn’t go smoothly—I somehow completed several multi-day backpacking trips and even the Uinta Highline Trail. I even said out loud on multiple occasions that I was actually enjoying quarantine, that I was enjoying my work routine at home, and that I liked cooking every meal every day. But by mid-September, something shifted in me.

I started making plans to go backpacking in the Cascades with my sister. She lives in Portland, so I figured I would park in her driveway and use her WiFi to complete some writing and podcast work on either end of the trip. That week, however, the entire Northwest burst into flames. Air quality was atrocious in much of Oregon and Washington, the sky completely orange from dawn to dusk. My mind swirled with these considerations:

- How do I deal with Covid-19 while visiting my sister? Should we both get tested and quarantine beforehand?

- Should we risk backpacking in fire-prone forests in the Northwest?

- Should we backpack in smoky areas with poor air quality?

- Is there a trip in that area that is both safe and non-smoky? How should I go about planning it?

- What if clashes between protesters and militias in Portland get worse? Do I really want to be there?

- Portland may have to be evacuated. Could I get caught in the traffic pouring out in every direction?

I procrastinated because I simply couldn’t compute all of this. Finally, it was too late. Procrastination made the choice for me, and although it didn’t feel right, I decided to head south alone. There were fewer fires in the Four Corners area so I could at least stop worrying about that, but I’d be alone, which would prove to be less than desirable.

These days many of us are far more alone than we have ever been before. To compensate for this aloneness, we connect to our friends, and sometimes people we don’t even know via texts, emails, calls, and social media. There’s a togetherness that screens allow, but it’s only a partial togetherness. I’m virtually never alone while being simultaneously nearly always physically alone. This strange state has left me in fear of complete aloneness, real aloneness. As someone who has backpacked alone countless nights, this fear of aloneness was new for me, and strange, and worth investigating.

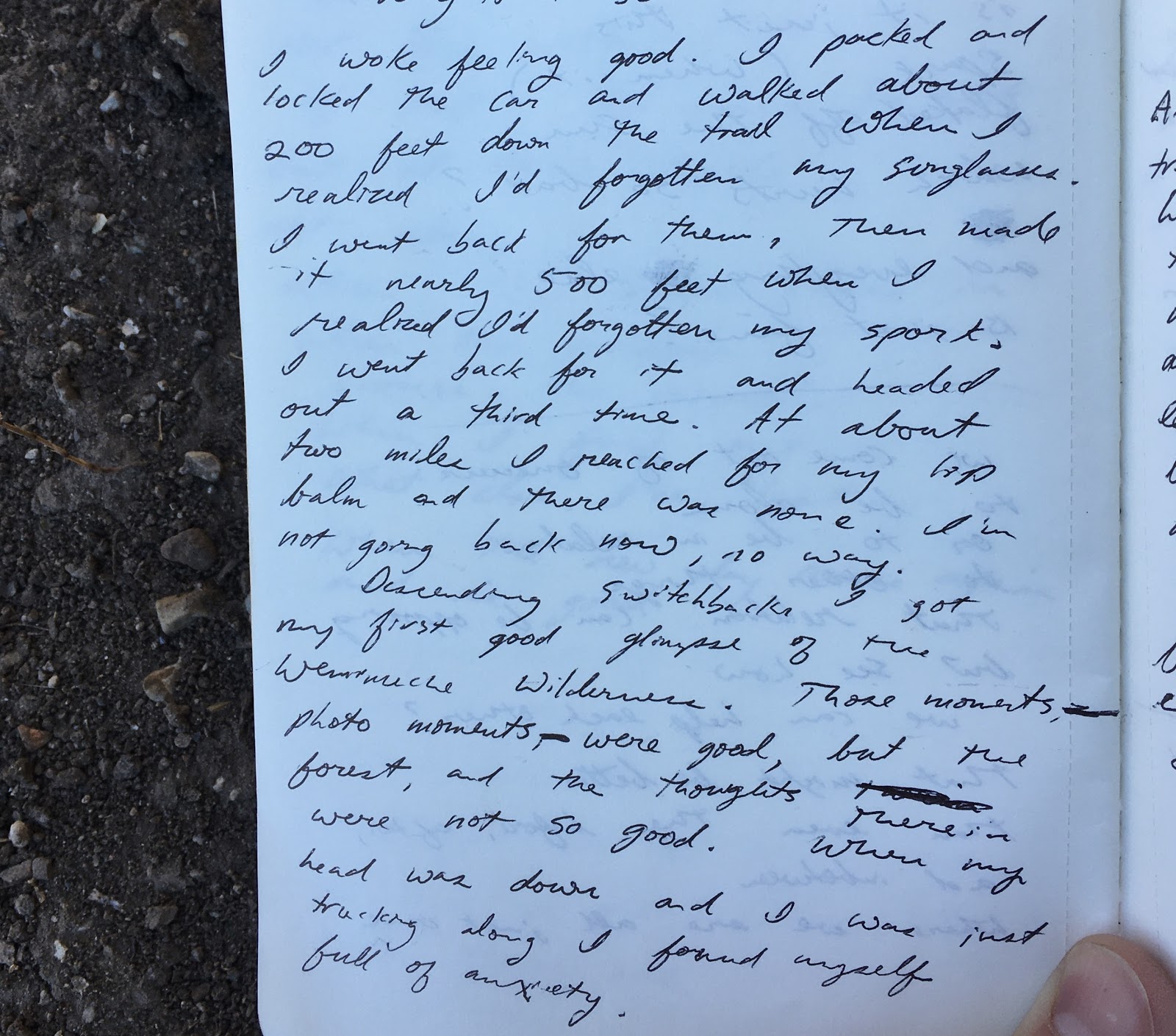

When I hit the road with a Weminuche Wilderness map on the seat beside me, I wasn’t quite ready to sever my connection to humans completely. Sitting in the truck after getting gas in Durango I sent some text messages out, hoping for an engagement—however mundane. Right before dusk I pulled into a campground and parked between ponderosas and gamble oak. A Steller’s jay greeted me from the picnic table. I stepped out of the truck and wobbled on my feet; I had forgotten to eat all day. After dinner, I walked out into the dark forest and stood and just looked into the darkness and the still-glowing sky beyond the trees. I thought about how all I wanted was certainty. Just certainty. Of any kind. In any aspect of life. I looked back towards the campground. And then I slowly made my way there.

The next day, when I walked down steep switchbacks between yellow aspens, I couldn’t get out of my head. The smoky sunlight shined through a dramatic valley with nearly 3,000 feet of relief between the mountain tops and the Animas River. These mountains were new to me and intimidating. I looked at the twisted rock across the valley which trees managed to grow sparsely on despite its near verticality and was awed, but my awe stopped short of appreciation. I stood on a footbridge that ran over the Animas with banks still slightly yellow from the 2015 Gold King Mine Disaster. I listened to the water, but it sounded far away as if I was observing it through a screen just as I’d been observing most of the world over the past few months. As much as I tried to experience everything around me, I really couldn’t. I simply kept ruminating, my mind spinning with uncertainty.

Later in the day, climbing a trail above the treeline I suddenly stopped. “What if it snows?” I thought. “I don’t want to be up here.” I hiked back down the trail and started looking for a camp in the forest. I scoped out a spot with too many dead trees and another that was too lumpy. Nothing was quite right.

Then I started second-guessing my choice not to go over that pass. I knew that it wasn’t supposed to snow, so why did fear of snow suddenly send me back down the trail? Moreover, I normally wouldn’t care one way or the other about snow, or I would even look forward to the beauty of snow-covered tundra at 11,000 feet. I felt like I just wanted someone to tell me what to do. Then I stood in the trees wondering why it was so hard to make any decision at all. I fell into extreme despair and just stood looking at the lumpy meadow in the afternoon light. Then I began judging myself for being unable to accomplish something previously so simple.

Depleted Surge Capacity

What’s going on here? I’ve been backpacking alone for years and yet I found myself incapable of something as simple as making a choice between walking over a pass or not. Even selecting a campsite was impossible. Apparently, I’m not alone.

Throughout the summer, I had been staying afloat by using what psychologist Ann Masten, Ph.D., calls surge capacity. “Surge capacity is a collection of adaptive systems—mental and physical—that humans draw on for short-term survival in acutely stressful situations, such as natural disasters,” Masten says.

I think of it as a form of adrenaline. We tap into it when we need it—to escape a mountain lion attack or a burning building—but it becomes depleted when we wake every morning only to find that mountain lion ready for the chase again. As the pandemic and other compounding uncertainties continue, and each day we grapple with the reality that things are still not how they used to be, our surge capacity eventually runs out.

I was unaware of the concept of surge capacity at the time, so I just stood in the trees judging myself harshly for not being able to accomplish simple tasks. I was still standing in the trees not knowing what to do when two men strolled by. The first exclaimed enthusiastically,

“Howdy! It just couldn’t be a better day, could it!?”

Caught off guard, I stammered “It’s, uhh, really nice.”

They walked on into the forest and I stood in the trail and watched them go. They’d been on the Colorado Trail for many days, so their appearance told me. I wondered what they knew that I didn’t. I wished I could absorb some of their happiness and ease through osmosis, and wondered if they were so much more settled than me because they’d been out on the trail for 10 or 15 days.

In the moment, the solution to my woes seemed clear: I needed more time out there. I needed to get used to being alone on the trail again. This could be true, but according to science journalist Tara Heale, in an article published in the online publishing platform Medium, pushing ourselves to function like normal might not be the best idea for some of us right now.

It’s Ok for Backpacking to be Hard Right Now

When I found myself fully and truly alone after the two Colorado Trail hikers disappeared, I became suddenly flooded with reminders of what I had lost in the past few months. Among other things, I’d lost the ability to hang out with friends or to go to the coffee shop, movie theater, gym, or restaurant and bask in the ambiance of others’ lives. I didn’t know the loss of these things would be such a big deal, as they’re less tangible than say, the loss of a loved one. This type of loss is referred to as “ambiguous loss”. Humans are wired to cope with acute loss or acute grief, but ongoing loss and grief are different. Heale writes that “ambiguous loss elicits the same experiences of grief as a more tangible loss—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—but managing it often requires a bit of creativity.”

One of the recommended ways of coping with ambiguous loss and the resulting depleted surge capacity is to expect less from ourselves. This means we should be OK with not being OK right now. I shouldn’t have beat myself up for my inability to hike over a pass, select a campsite, or enjoy the trip. It’s even alright not to go backpacking if it makes things worse. Backpacking often necessitates the use of problem-solving skills, physical strength, and mental and emotional robustness; all things that may be depleted for some of us during this strange time. And this is particularly troubling when backpacking—my primary form of stress-relief and self-care—suddenly turns on me.

It’s a pretty hard reality to accept, but accept it I must. Of course, many folks reading this will not be in the same boat as me, and for them, it’s fine to go backpacking more than usual if that’s what best relieves your stress. The bottom line is we need to do what we need to do to take care of ourselves regardless of how that might compare to the ways we cared for ourselves prior to 2020. Backpacking isn’t going anywhere, and things will not always be like this. Remember, we have the summer of 2021 to look forward to, and it’s going to be amazing.

Further Reading

https://elemental.medium.com/your-surge-capacity-is-depleted-it-s-why-you-feel-awful-de285d542f4c

Related Content

- More The Overlook by Ben Kilbourne

- How to backpack safely as Covid-19 continues to worsen

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

- Product mentions in this article are made by the author with no compensation in return. In addition, Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for product mentions or placements in editorial coverage. Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light's gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you'd really like to support our work, don't buy gear you don't need - support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead. Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear.

Home › Forums › The Overlook: Backpacking in a Time of Uncertainty