“The road seen, then not seen,” begins the poem “Santiago” by David Whyte.

The road seen, then not seen, I think, walking down Woodenshoe Canyon in Bear’s Ears National Monument in late November. The red trail below my feet leads into piñon and juniper and turns and disappears within them. The path seen, then not seen. It dips into a willowy wash and is nearly gone, only seen where snake grass is occasionally matted down by past feet. The road seen, then not seen.

If you would have asked me when I was 20, I would have told you I expected to be married with kids at 35. It’s just what people do; it was inevitable. But it wasn’t a road I actually saw; it was imagined. All I did see was a narrow rocky path leading to hobbies like backpacking and various dead-end jobs and disappearing behind them. Only the next ten feet or so were guaranteed; it’s usually impossible to know what’s beyond that. Now I’m 35 and I am neither married nor do I have kids. I’m also newly single, walking through a canyon I’ve never before seen, on a trajectory I never before expected, with a future completely unknown. The trail seen running through ponderosas, then not seen winding behind sandstone cliffs hundreds of feet tall.

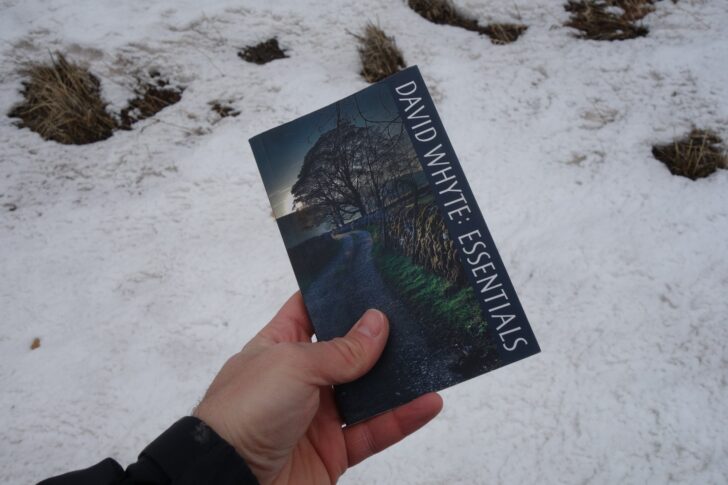

I usually pack a book (or two) in my backpack, and in 2020 I took the book Essentials by poet David Whyte on almost every trip. It’s small and light (3.8 oz / 108 g) and has striking things to say about a host of experiences all humans share. I’ve pulled it out during lunch breaks on salmony slickrock overlooking willow-bottomed canyons, and I’ve read a few poems tucked in my sleeping bag at the end of a long day. While the whole thing is incredible, as a backpacker, the poem “Santiago” landed hardest. He wrote the poem for his niece when she walked the Camino de Santiago, the famous 500-mile (805 km) pilgrimage to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain, where remains of the saints are supposed to be buried. I’m sharing it here because people embarking on long adventures may relate.

The poem continues:

and the way forward

always in the end, the way that you came, the way

that you followed, that carried you into your future,

that brought you to this place

Despite knowing nothing of what is ahead, there always is something that draws you on. In the context of a thru-hike or other long adventure, it is at first that belief that there’s something out there that is better than right here inside your apartment, looking out at the gray street where the cars and pedestrians seem like automatons moving along it. The mundanity of cooking in the same kitchen, working at the same desk, and eating at the same table is surely less interesting than whatever you will find along the trail. So you plan, pack, and leave. And when you are finally walking that trail between Mexico and Canada, you may feel

the sense of having walked

from far inside yourself out into the revelation,

to have risked yourself for something that seemed

to stand both inside you and far beyond you,

that called you back in the end to the only road

you could follow…

…so that one day

you realized that what you wanted had already

happened, and long ago and in the dwelling place

in which you had lived in before you began,

and that every step along the way, you had carried

the heart and the mind and the promise

that first set you off and then drew you on

and that, you were more marvelous in your

simple wish to find a way than the gilded roofs

of any destination you could reach

Years ago, when I took a job as a wilderness ranger in the High Uintas, I did it in part to feel some sense of accomplishment. And I did it to see what would happen if I was out there for four weeks, eight weeks, twelve weeks. I was certain that the place would provide the revelation I needed to turn my life around back home. I waited countless nights for a revelation of some kind beside Betsy Lake, a football field-sized, oblong, dark teal lake hidden deep in lodgepole forest. Clouds shot out from behind West Grandaddy Mountain, a castle of crumbling gray and pink sandstone, and careened over me, mirrored in the glassy water. It would pour in the evenings sometimes and I would walk in my dripping raincoat from my camp in the trees out to the shore to find the surface turned to static.

Day after day and night after night I walked, listened, and waited. Sometimes I didn’t even enjoy my time in the mountains, and I found myself wanting to be horizontal on a couch watching a movie. I put in big miles, I spent entire tours almost entirely alone, and I watched the sky change. But it was none of these things nor osprey dive nor lightning strike which was the ultimate revelation. When the season wrapped up and fog lay across the water, whortleberry leaves had turned from green to red, meadow grasses had turned yellow with specks of orange and red, and I stepped inside the government rig and drove back to town, I felt different. “I did this,” I thought. I found strength and felt accomplishment finally in my desire to search for those very things.

That was the revelation. It wasn’t external at all. It was indeed the promise I carried with me, the desire for revelation, the desire to find something. It was indeed that I was more marvelous in my “simple wish to find a way,” than anything I found out there.

In a brief commentary on “Santiago”, David Whyte reminds us of the poem “To go to Rome,” which reads, “Great the journey, little the gain, if you do not carry Him with you you will not find Him there”. God here, of course, is a metaphor for that “simple wish to find a way,” that desire, the ambition to try. Whatever prompted you to plan, pack, and leave in the first place was always within you.

as if, all along, you had thought the end point

might be a city with golden domes, and cheering

crowds, and turning the corner at what you thought

was the end of the road, you found just a simple

reflection, and a clear revelation beneath the face

looking back and beneath it another invitation,

all in one glimpse: like a person or place

you had sought forever, like a broad field of freedom

that beckoned you beyond; like another life,

and the road still stretching on.

How many of us have gotten to the end of a trip to find only the car waiting for us? No cheering crowds, no finish lines, no plaques engraved with our names. Many times I have walked up to the car, leaned my trekking poles against the side to begin fishing around for my keys, when I see myself right there, reflected in the dusty window. I may have forgotten my name at some point on the journey; I may have spent entire days unworried, my troubles buried under miles and wide vistas, but in the end, I am still me. Everything I started with – the good and the bad – stayed with me the whole way, returned with me to the car, and will be traveling with me to my home where I began.

And how many people have gotten to the terminus of a thru-hike a day earlier than expected, approaching the monument alone in the quiet rain, looking at it, and then walking into the trees to spend one more night alone before your ride arrives the next day? No fanfare, just the end of the trail, “and the road still stretching on.” If, after months on the PCT or the AT, you found that what you searched for out there was inside you all along, did you have to do it? Did you have to go out there and hike hundreds or thousands of miles to gain this understanding? I don’t have an answer for that.

You’ll probably have to hike to find out.

David Whyte’s “Santiago” is a clear-headed contemplation of the entirety of a thru-hike, from a hiker’s intention to the first step on the trail to the anticipation of revelation or external validation, to finally realizing what the whole thing was about. Anyone planning a hike of any length (but especially the longer ones) should consider reading this poem beforehand or better yet, taking it with you. “The road seen, then not seen,” it begins.

Further Reading

Related Content

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

Home › Forums › Take This Poem on Your Next Trip