Who or what makes a trail?

I’ve often wondered this when veering off the Bonneville Shoreline trail that skirts the edge of Salt Lake City to investigate less distinct deer trails. The Bonneville Shoreline trail is a human trail today, no doubt, but when Lake Bonneville lapped at the shore between 30,000 and 13,000 years ago, bison, deer, and later Shoshone, Ute, Goshute, and other Native people surely walked the edge of the water. Then when the lake receded, it left a clear line, an obvious promenade just asking to be walked. So, who or what created this trail? Did the lake itself make it? After all, today’s trail is named after the lake. The existence of this question seems to speak of its own futility, or maybe trail-making or path-making are just more complex than they appear.

The word trail is used to describe the well-worn way through the woods where brush has been cleared and lichens scraped from the rocks by boot soles or the cairn-marked route across the slickrock. Some are more imaginary than others, but we call them all trails. As a noun the word means “path or track worn in wilderness,” but it functioned as a verb long before that. Trail can be traced back to the Vulgar Latin tragulare meaning “to drag,” later the French trailler meaning to “to tow; to pick up the scent of a quarry,” and later yet “to hang down loosely and flow behind,” like a sleeve.

Walking a sidehill trail through yellow grasses and scrub oak, I wonder what the deer is dragging through the wilderness to wear this line across it? Her very essence? Some sort of spirit? Maybe trail as a noun is the impression left by the life-force (whatever that is) trailing behind the body like a gown. A sort of watermark. A reference to the ghost. A finger pointing “she went this way.” Or a voice saying “she is always here, even at this moment; everyone who ever passed is still passing.” Maybe.

In some parts of the world, trails are more commonly called paths, walkways, or footpaths. As is the case with many words, there isn’t a consensus on the origin of the word path. The Old English paþ or pæþ was a “narrow passageway or route across land, a track worn by the feet of people or animals treading it,” and it probably derived from the German pfad, but prior sources are confounding to etymologists. The closest relative to the modern path may be the Avestan (an old Iranian language) pad, which holds the same meaning as path, but no one knows for sure. In any case, definitions of trail and path both led me to the word track.

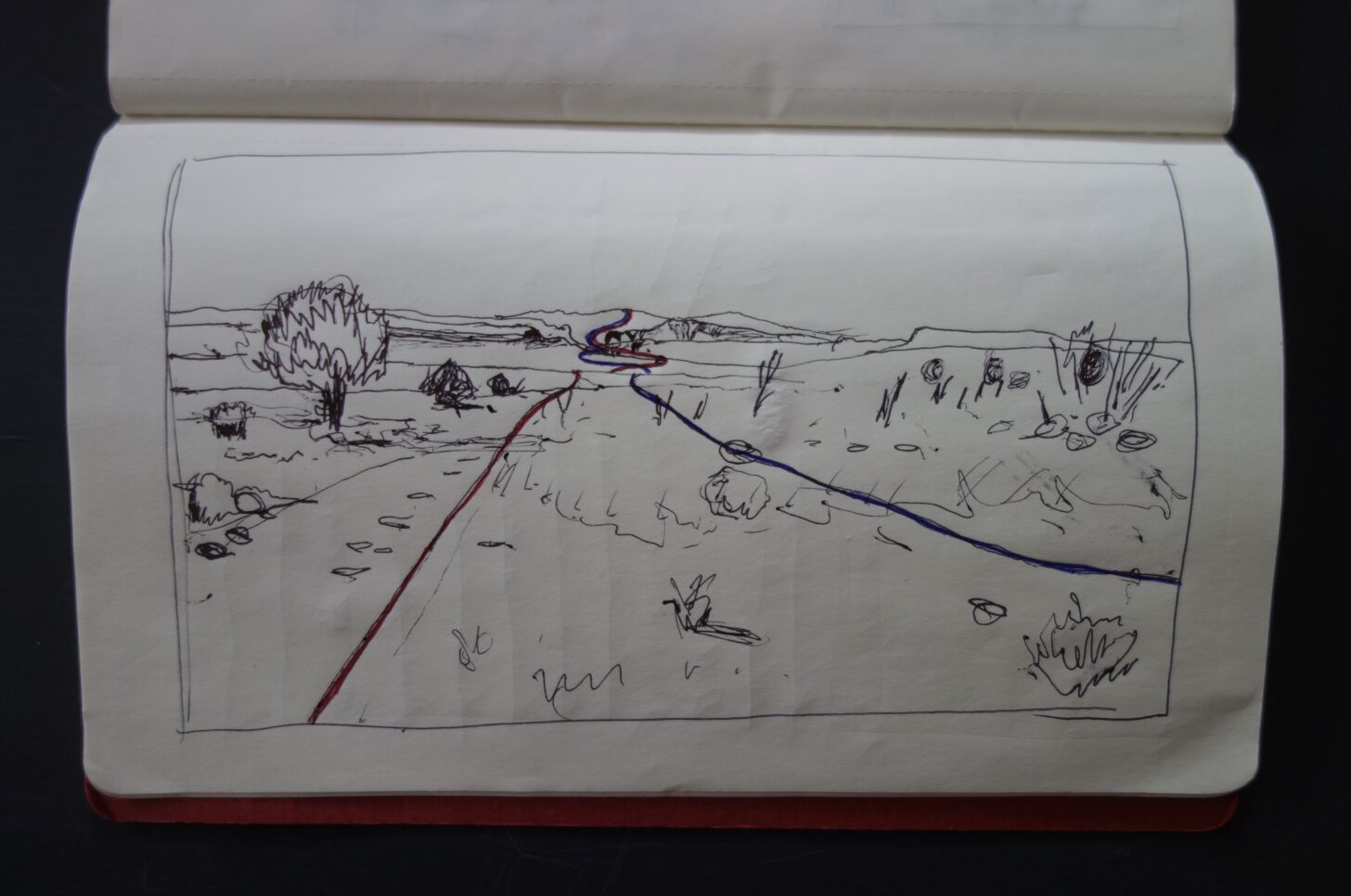

Track means “marks left behind,” and can be traced back to the Dutch trek meaning “draft” or “drawing.” Is that what we’re all doing when trekking, taking the paintbrush or pencil that is the foot to the page that is the earth? As an artist, there’s something I really love about this idea.

Footprints Wherever I Go

Consider the line that is drawn when simply trying to find the easiest way from here to there. I walk without thinking and take the most gradual slope into a wash, follow it down, and take the most gradual way out. I see a dense copse of junipers and go around them. In a canyon bottom, I zigzag between willows, always looking for the widest gap, the most permeable route. And all the while, nearly 100% of the time, there are footprints wherever I go. Coyotes, deer, elk, bobcats, cows, horses, and humans alike chose the route that expends the least amount of energy. There is always a best way to transect a landscape, and most creatures intuitively find it.

We are collectively drawing the way that connects the land and the animal. What remains is a piece of art that is a testament to that interconnectedness.

If the trail, track, or path is a shared creation, made by the land just as much as the traveler, this means the land is more than just medium, it’s also actant, so it has some degree of agency. The trail I walked today in the Uinta Mountains traced a creek from sagebrush up through gamble oak and ponderosa to lodgepole pine and Douglas fir. It was well-worn, almost smooth in places. Trail crews cut trees year after year, so even if the trail itself was somehow suddenly gone you’d still know where to go, there’d still be a corridor. Check dams, water bars, and steps were constructed here and there to increase the longevity of the trail and prevent erosion. Within a mile, the trail crossed the frozen creek at a bridge and later crossed back over another bridge.

These things, the human structures that make travel easy, were not always here. But the creek was, and the first travelers: deer, elk, or moose moving from the willow bottomlands to the high country pushed by the cold or the heat. They took the path of least resistance. They followed water, letting it build the trail with them. Or they followed forage, letting the seemingly random lay of the land guide them. Beyond the animal and the land, the seasons are also trail builders, how they nudge animals with more than just a little urgency to move if they want to stay alive.

Now lodgepole die and fall, and forage shifts in the climate-change era. The artist carefully draws the familiar line, a testament to interconnectedness, as the table is bumped, and the steady mark goes careening across the page. Afternoon storms are less frequent. The inkwell is spilled on the page, the brush is forgotten overnight and found in the morning caked with paint. The artist returns to the page with a pencil, trying to remember where to go, but it looks different now. Swaths of forest are burned and neon aspen shoots emerge from the black. Old springs trickle out into the devastation, pushing aside gray ash. The artist looks for the path of least resistance and draws again through the forest, past lost springs, sniffing out new ones. The artist can’t just stop. There’s always a trail to be made.

Ben’s Switchbacks

When I was 18 years old I built a trail in the hills outside of my hometown. It began near a creaking pump jack and climbed a hill, the switchbacks weaving between piñon and juniper. I followed no previous tracks, instead endeavoring simply to make the hill accessible to myself and other humans. At the top, one could walk or bike a rocky spine and then descend a more gradual hill back to the start. It’s now part of an official trail system, with a sign reading “Ben’s Switchbacks,” which gives people someone to blame. Mountain bikers can curse the amateur trail builder Ben (whoever that is) when they find themselves unable to clean every switchback. Too steep. Not enough of a platform for turning a 29” wheel. Oh well. I didn’t know what I was doing.

All I knew was that I wanted to make a path up the hill; I couldn’t articulate more than that at the time. But maybe I wanted to make something that would allow people to better experience the landscape without having to focus too closely on each step. Something about trails frees up your attention, where bushwhacking often steals it, and we get to know a place more easily. Maybe this is what drove me to make the trail, it’s hard to say. Maybe this is the impetus behind many human trails, I can’t be sure.

Sometimes when I visit my parents we walk Ben’s Switchbacks together. I ponder the trail’s existence, my singular desire to create it. I wonder how it may differ from the creation of other trails: the Bonneville Shoreline Trail, the Natchez Trace, the Appalachian Trail, or the little deer trails that draw lines through the snow in the foothills outside of town. I wonder if my individual agency—my desire to create—is really all that different from the collective agencies who drafted these other trails. Likely it’s not.

Related Content

- More by Ben Kilbourne.

- Read Andrew Marshall’s book review of “On Trails: An Exploration” by Robert Moor.

- Thinking of leaving the trail? Get some advice from our forum first.

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

- Product mentions in this article are made by the author with no compensation in return. In addition, Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for product mentions or placements in editorial coverage. Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light's gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you'd really like to support our work, don't buy gear you don't need - support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead. Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear.

Home › Forums › The Anthropology of a Trail