From Phil Arnot to the Sierras

I wanted to experience the mountains fully. Not just the common trails and sunlit vistas, but the down and dirty, uncompromising, mud-encrusted mountains. I wanted the fearsome backcountry of Jeremiah Johnson and The Revenant. I wanted drama, rain, and thunder. And, my oh my, did I receive it.

As with most adventure enthusiasts, my forays into the wild began with the far safer and significantly less humiliating enterprise of reading. This went back to adolescence with such novels as Island of the Blue Dolphins and Hatchet, tales that featured far less dismemberment than their adult counterparts of, say, Into the Wild and Alive! My fascination persisted well into adulthood when, following such trite digressions as career, marriage, and child-rearing, I could be found each evening scouring all manner of map and memoir in search of destinations.

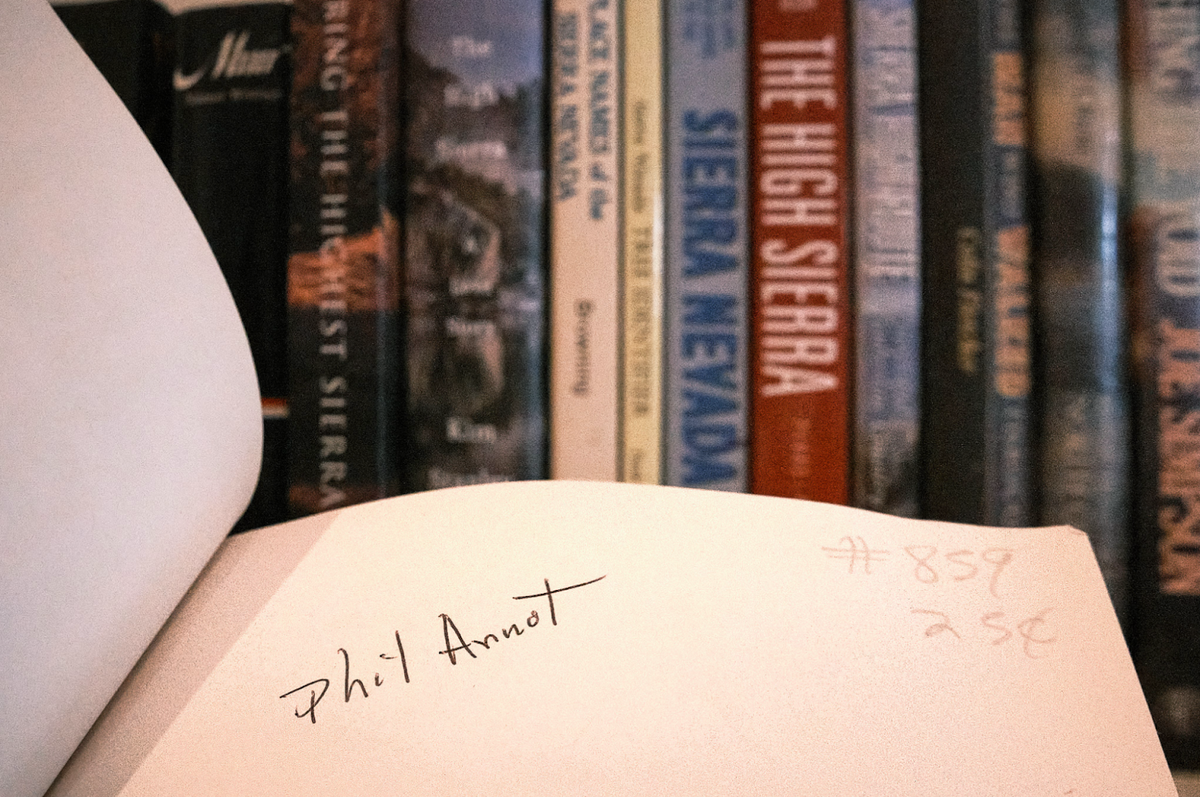

I had caught wind of a paperback, rumored long out of print, whose lofty prose could fashion bona fide swashbucklers of the lowliest day-hikers. The book was High Sierra: John Muir’s Range of Light by Phil Arnot, a title unavailable not only in hardcopy but impossible to download from any corner of the internet.

This only heightened the book’s mystique, and after four months’ vigilant monitoring of eBay, I at last tracked down a copy. It was marked as in “very good” condition, with no mention of “like new” or “mint”, no claims of storage in climate-controlled facilities or UV-filtering partitions. The listing was accompanied by a single unfocused photo in which the book was clasped with unnecessary vigor by a hand that appeared to have been recently doused in motor oil. And for this the seller wanted $125. It seemed a reasonable asking price for perhaps a lesser known Picasso or the mustache clippings of Charlie Chaplin, but for an obscure title from a publishing house whose catalogue included such offerings as “Greek Cooking for Everyone” and “The Joys of Mathematics” it was near enough a robbery.

Hurriedly, I devised a plan to pawn and auction off and variously liquidate what clothing and furniture I could manage without exciting my wife’s attention, and within a week the book arrived: a simple paperback of modest construction with the curious double-columned layout of high school textbooks and—to add insult to injury—a price scrawled on the inside cover from a previous sale of 25¢. If ever there was a cosmic lesson about the dangers of reckless spending and the illogical extremes of the free market, this was it.

My profligacy aside, the writing was as illustrious as could be hoped for. In lucid and stirring prose, the author advocated for mountain meanders well off the beaten paths – as in, an infinite distance from them. Certainly a good distance farther than I had, as of yet, explored, considering the bulk of my experience was gained while in a living room recliner.

Among the colorfully atypical amusements to be found in the Sierra, Phil Arnot recommended the pleasure of a lightning storm. While a gigajoule of electricity lanced haphazardly from the heavens might not register with the average backpacker as “recreational,” Arnot wholeheartedly endorsed it.

And so, armed with the well-worn guidebook and slightly insufficient rations, I made for the Sierra. Did I set out to test myself? In part, but only as a gourmand seeks the challenge of a buffet. Success was all but assured—what could possibly go wrong?

Paradise Valley

For two days I traipsed with relative ease up from Road’s End through Paradise Valley and to a pristine alpine lake, the precise spot from which Phil Arnot enjoyed his brush with homicidal weather. With characteristic understatement, he called it “the grand show,” an experience he qualified as among “the most indelible in fifty years of roaming up and down the Sierra Nevada.”

But one would expect no lack of edge from a man who in the same book gleefully praises the joys of braving winter snowstorms, spending nights exposed at altitude, and stops just short of vouching for an invigorating tumble from the nearest clifftop. After all, this was a man who, while piloting a B-17 in twenty-one offensive missions over Germany, amassed a service record of such distinction that foreign governments felt compelled to shower him with medals; a man who passed the winter of his life not in some Floridian retirement center, but in a spartan log cabin built by his grandmother in the 1920s; a man who, frankly, no aspiring adventurer could help but emulate.

And so, while patiently awaiting a weather forecast that called for a watery end-of-days, I put no more thought into properly outfitting myself than I imagined Arnot had before any of his countless wartime missions. I carried with me an entry-level tent, inflatable mattress, and assortment of freeze-dried food. Notably absent were life preserver, scuba tank, and pack raft.

During the first two days’ hiking, I encountered only a light drizzle and anticipated making no adjustments to my intended route on account of weather; I’d simply enjoy the “grand show” until it grew tedious, then strike camp and nimbly scamper over the high pass and down the intervening mountains. Images of a gentle stroll beneath the plentiful cover of redwoods during the most benign and picturesque of sprinkles had instilled in me a dangerous degree of unearned confidence.

After pitching camp at the lake in nothing more troubling than a stiff breeze, I began to wonder if bringing along even my rain jacket had been necessary. (I later learned the old backpacking adage of “don’t pack your fears” fails to mention that one should pack, if not their fears, at least some common sense.) Following dinner I fell asleep and some time later awoke to rain. Hard rain. Heavy rain. Rain that pelted my tent as though to ward off my intrusion. It was not altogether clear if I was in fact awake or dreaming.

The next morning, the sky was clouded heavily and the breeze had gained momentum. And yet no downpour. For all the fuss Phil Arnot made, his grand Sierra storm seemed little more than weather fit for slightly subpar sailing.

Of Storms and (Il-)Preparedness

I began to strike camp, intending to continue up and over the granite ramparts which fortified the southern valleys.

“Heading back?” a woman called from the rocky flat just below me. She had a single black wing of hair that fluttered madly in the weather. Marshaling it beneath her collar, she tutted twice in disapproval, and approached with that motherly air against which all but mothers are defenseless. “You’re not making for the pass?”

Mustering my most Arnot-like inner swashbuckler, I concluded—if in a higher register than was preferable—that I had not hiked through such wild country to be afraid of a few raindrops. I turned my palm up as a saucer to catch the silk of dew and presented it to her, as if this would close the argument irrefutably in my favor. As I did so, a clap of thunder rumbled through the basin. Certainly signal enough to convince even the most moronic to go no further. This was the calm before rough weather which Search and Rescue workers affectionately termed “the sucker hole.”

I conferred with my cherished guidebook and happened on the following description: …the rain turns to hail as hundreds of white pellets spit downward onto the meadows, bounce three or four inches back into the air, then settle on a growing mass of white carpeting.

A charmingly tranquil wonderland, as Phil Arnot painted it, without the faintest whiff of mortal danger.

Kat and her compatriots, who had by now shuffled forth to face as a judge and jury, were not so hopeful. Glancing at intervals toward the roil of clouds behind me, they insisted that trying for the pass now amounted to no more than a stylized execution.

Kat cinched her lips in fierce displeasure, tut-tutting once again, and I heard myself—still in a ringing falsetto—agree to turn around.

And so it was. I would have to catch the grand show on the move, if it was ever to arrive. Kat, content that I would shortly decamp for lower ground — and eat my vegetables while at it — returned to her campsite to assist in the rolling up of sleeping pads, the buttoning of rain jackets, and the application of rain covers to backpacks, notoriously finicky things.

“Need help with yours?” her mustachioed hiking mate called as I made ready with my gear. And here we reach the crucial moment, though I didn’t know it at the time, which was to color my next eight hours.

“Rain cover?” I called back easily, “No. I didn’t bring one.”

Let me digress momentarily to Kim Stanley Robinson, Sierra enthusiast and author of what is arguably a benchmark on the subject. Sadly, Robinson is also an ultralight nut, and after reading his book, The High Sierra (one would expect, for all their talk of nature’s inspiration, that these authors might utilize some of it when naming their releases. To this point, I currently have on my bookshelf the following titles: Sierra Nevada; High Sierra; The High Sierra; and, remarkably, The Highest Sierra), I was utterly convinced that my success in attempting a twelve-thousand foot pass, in addition to my well-being and happiness in general, relied entirely on shaving every ounce possible from my backpack. Thus the mini-water filter which left me laboring at each stream as though milking a stubborn heifer, and the notion that my tent’s rainfly could just as easily double as a backpack cover.

What ingenuity! What daring! What complete and utter bullshit.

I withdrew the crumpled rainfly from my backpack and proceeded to struggle with the material as though engaged in a fight to the death involving a malicious length of nylon. It snarled first on my carabiner, then hooked resolutely to the handles of my trekking poles. My backpack, an ultralight model, was constructed of a gossamer fabric with a durability and water-resistance roughly equivalent to cotton candy; should I fail to cover it entirely, I risked making camp at day’s end with a sodden sleeping bag and nightclothes. Hypothermia would ensue directly, followed by a protracted and disgraceful death in which—once more in warbling falsetto—I would whine for my mother, or for Kat.

In desperation, I flung the nylon blindly out behind me, then turned in circles much like an idiot, trying to check how it had landed. Labradors have chased their tails with more dignified precision. At last I settled with the rainfly worn as an old-world babushka. In order to keep it positioned correctly, both my hands were forced to clutch at thick sheaves of the nylon. This seemed to work, except for the fact that I now could not walk properly. I now could not walk even reasonably. With each trekking pole’s extension the rainfly was stretched to breaking and I was yanked forward, off-balanced by my own momentum.

Clearly this would not do. As the drizzle intensified to rain, broken now and again by rolling thunder, I was reduced to carrying my trekking poles before me swathed in the nylon excess. To all appearances, I was stumbling through the downpour over hazardous terrain, dropping from above ten thousand feet, while carrying a swaddled infant.

I made for Paradise Valley; a slog of sufficient length to properly savor the scrape and graze of rainfly against my clavicles. My earlobes suffered in similar fashion. There was a general chafing of wrists. I was tormented on every hand by unexpected gusts of wind that swept the nylon across my mouth in an attempt to waterboard me.

After several hours of application of the rainfly as cape and backpack cover and prayer shawl, each by turns, I was not only completely soaked but mentally exhausted. The downpour broke in earnest, advancing from seasonal to catastrophic. Thunder clapped in such a fashion that the metaphor held true. I was now witness to the full measure of Phil Arnot’s grand show—a pleasure which harkened back to oral surgery or a striking bout of diarrhea.

Trundling feebly, I neared Woods Creek and found the trail junction deserted. I dashed between covering pines and found that they did nothing for the rainfall. Water was everywhere, omnipresent in thunderstorm and sweat and river. The sky had swallowed an ocean and was now vomiting it down.

Of Friends Made and Lessons Learned

“Hiya,” came a nasal voice, mere inches behind me.

I spun in a confusion of pleated nylon which came to rest over my face. Shoving it aside, I found before me an extravagantly bearded man in a thin windbreaker and gym shorts, munching on a bag of Fritos. In this end-of-the-world maelstrom, he seemed distinctly unconcerned with any aspect of survival, save tonguing of cheese powder from each of his splayed fingers. This was Alex; and it must be said that, foliage and wildflowers aside, the Sierra is home to what must be some of the planet’s most exotic facial hair. The growth which obscured the lower half of Alex’s face seemed well into the process of establishing outposts along his nose, outflanking his eyebrows, and strategically maneuvering so as to overrun his face completely.

Alex was thru hiking the PCT northbound and allowed that this was the fiercest storm he’d yet encountered, and did I know black bears produced milk, and did I think it tasted fishy? Had I heard of “10-by-10s”, the distance practice of speed-hikers? Where did park rangers vacation? And would I like a Frito-Lay?

And on and on like this, expounding on an arbitrary range of subjects—a monologue in which the influence of intoxicants was not altogether inconsequential.

“Hey,” he said at once, inquisitive, his glassy eyes hovering around me, trying to settle. “You know you’ve got a rainfly on your head?”

I thought to reference Phil Arnot’s guidebook as to wildlife encounters, but had to fend off a jagged corn chip.

“Want one?” Alex shrugged off my demurral and sniffed deeply of the Frito as one might a prized cigar. Of the nearly six hundred million people roaming the continent, I could think of none worse to drown beside than a man who regarded deep-fried cornmeal as the zenith of all creation.

I was experimenting with teepee formations of the rainfly in order to stanch the pooling of rainwater at my elbows when came the distant call of voices. Up a sparsely forested rise I glimpsed the slick pastels of raincoats. Kat and her group was reconnoitering the massive suspension bridge which spanned the rushing water. I hurried to them and was greeted with a tsk-tsk of disapproval. “Look at you, you’re shaking. Here, come on across the bridge.” Kat ushered me to the rear where I awaited what appeared to be imminent death by drowning.

The bridge was one of those wavering constructions that would be perfectly at home at an unregulated county fair. Its slack cables gave ample leeway for the deck to swing and wobble and variously undulate so that none could hope to safely cross it. A sign tacked to a tree warned grimly, One person at a time.

I watched as Kat and her compatriots crossed the bridge in brisk succession and did my best to follow suit, trailing in an all-out sprint, blundering madly, my left hand busy clutching at the rainfly and my other grasping for dear life at each of the braided cables. Lightning was showing now, flat white in all directions, as if to remind me that steel suspension bridges and high-voltage charges did not mix.

On the far side of the water, Kat’s group had strung a 5 x 5 tarp between the trees into which we tumbled, jostling politely to ensure each had their place. There was an orderly pleasure to it, agreeably at odds with the frenetic air of the past few hours. Fears which had gained the rash momentum of flatbed trucks with faulty brake-lines now eased to a halt amid bear canisters, scattered foodstuffs, and jaunty conversation. The small blue tarp, drumming with downpour, took on the intimacy of a dinner gathering—which it had become. A loose assemblage of health and candy bars, saltines, and foil envelopes of chicken salad now crowded what was already a miracle of contortion. That none of us was edged into the rainfall or forced into improper contact (that would have been a different sort of gathering entirely) was itself a proud achievement.

The gathered party was soon enlarged further by the introduction of a bearded face, its lavish mass enlivened by a fragrant orange dusting.

“Frito-lay, anyone?” asked Alex, forcing his way beneath the tarp and generally making himself at home, shifting bottles and backpacks to the margins so as to clear himself a seat.

“What,” said Kat, regarding me closely, “now you’re not eating? You know that shivering burns calories.”

It was true, the surplus of sweat trapped by my rain gear and the rainfly had chilled me deeply.

“Here,” said the young girl, plump-cheeked and rosy, sitting to my left. She tendered a smear of cheese with the blunt tine of her spork. “You can have it,” she smiled, blinking with some ocular dysfunction. She wore a pair of glasses whose depth made one feel they viewed her down the wrong end of a telescope.

“What is it now?” Kat piled on. “What, don’t you eat lactose?”

The young girl nodded, still blinking. “It’s Muenster.”

It had been at some point, surely.

I have no doubt their intentions were spotless, but the smear of cheese was not. It had developed a multi-colored skin and conspicuous dry patches that required a pathologist to fully diagnose, not to mention a tacky center one could fairly call life-threatening.

Sensing my hesitance, Alex blurted, “Maybe he’d like a Frito-Lay?”

I held the cheese at a safe distance and then, at Kat’s insistence, I relented. The complex mouthfeel and flavor profile were, as Phil Arnot would put it, indelible.

And perhaps they were. Perhaps this is exactly what Arnot meant to encourage — to put oneself at hazard, whether by lightning strike or Muenster, is to circle back on evolution to a time when survival hinged on matters somewhat more elemental than mortgage schedules and stock options. No stranger to discomfort, Arnot clearly understood this; that joy was not always joy and pleasure not always pleasure.

The rain had tapered. The food ran low, and the gathering disbanded.

Before departing, Kat helped to reaffix my rainfly, weaving its guylines into a sort of yolk about my sternum that ensnared my pinkie finger. I watched her group march off into the forest and Alex meander to god-knows-where, then, with a delicate twist of creases, I set the rainfly back into position.

As I wandered downhill along the trail, my gait lengthened and grew more steady. I was at ease now, watching the clouds, nodding my imprecise approval. A balmy mist twisted pastoral. The wash and fold of laundered currents. A pocket meadow burst with lilac and a weft of daffodil. I had surrendered all concern of death by drowning, or by lightning, or any other brand of improbable misfortune for long enough to take notice of the splendor which surrounded. I thought of Phil Arnot once more, hard-grained and handsome, sitting down with a wry grin to pen the words that, for those foolhardy as I, carried all the hazard of a shotgun.

But I had survived the endeavor and was no worse for wear. A bit humbler, slightly more

damp. Was I in some way better for it? I suppose so, in spite of everything. $125 better?

It was hard to put a price on.

25¢ for certain.

Home › Forums › I Got Caught in a Sierra Storm, on Purpose